Death has no answer: a dialogue about life extension and limits

in memoriam R.G.W.

– Dong, Dong, Dong!

Who’s there?

It’s me, Charon, getting ready to depart.

You, the infernal ferryman! Why are you tolling the bell?

I’d thought you’d want to know.

You’re unsettling me! I’m in a good place now, in my study and lab, in good health, and practicing ways to preserve health and extend lives.

I’m leaving.

Who is with you? Why should it concern me?

There are people you will miss.

Someone dear to me? Can’t you wait?

No, the race is run, the boat must leave the shore.

Why now? I’m not ready to hear this. I’m concerned with other things: improving society, culture, people’s minds. I want to travel, make more money, and be with my family and friends.

There is a time everything must end.

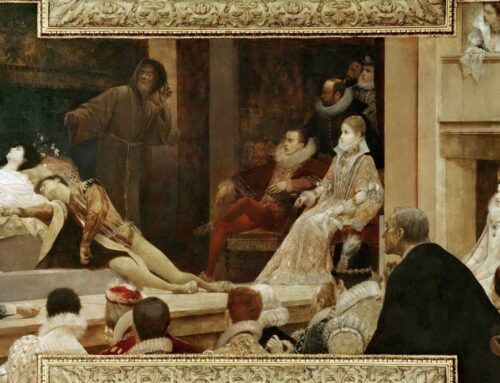

This is so wrong. I want answers. Do you think that death can suddenly disrupt my life, like a medieval skeleton dancing with my friends, or a ghastly chess player pushing them toward the final match? These are antiquated ways, Charon, as are you, a mere myth, like Macbeth’s witches. I don’t want to waste my breath on this. I have other problems to solve.

Mere myths, as you call them, may show you deeper meaning. Is there a greater problem than this?

No, but even so we’re working on solving it, discovering how to lengthen our telomeres, and to tinker with our DNA. Science and technology will continue to eradicate disease, solve crises of hunger and suffering. The future is bright.

It may seem bright. But it is finite for each of you, as for those you know.

Who is that with you?

You know him.

Yes, I do: a good man, most generous, an imaginative and careful scholar, honest in all respects: both the exemplar and exception to his craft. He was a mentor, who spoke clearly about my mistakes yet also appraised my strengths. From him I found support and my footing in my career.

You must see him go.

If he goes, then, as they say, part of me goes with him. I cannot accept that he is gone. Death must answer for this grief, this separation.

You ask for answers, but there are no answers for death. I have seen so many like you: unconcerned about this fact of life, carefree in your career, as if every year brings a revolution of the same. You watch your children grow up, while ignoring your own passage to this place. There will be a time, too, when you will cross this river. How can you study the past, or research the puzzles of ancestry, and yet fail to see, first of all, how you only occupy your world temporarily, at time’s pleasure. And time, in Shakespeare’s words, must have a stop. The stop has come for your great friend, as it has for your parents. This history – so small, in your studious grand scheme – has determined your life. You live toward death: there is no other way.

Yet we hope to live.

You must set this hope of living on, ultimately, to the next life, beyond this river. The fact is death, and the hope is life. This hope is found in the certainty of belief, not observation. How many doubt this belief, while also ignoring this fact! Like you, they search desperately for hope in science, or faith in technology, or comfort in reputation, and chase these chimeras. All the time, I must do my job. Your friend has passed from your life.

I am in grief, and still protest. Maybe now I understand his greatest lesson. In his final months he never stopped teaching me about the dignity of life, for he bore his failing health with great presence of mind, and without becoming overwrought by his increasing weakness. I cling to this: that though he has passed, part of him remains. It is this part, in memory, that still enlivens my life.

I hope so. Farewell.

Leave A Comment