Out of the woods: no trees at the library. From our Vatican City correspondent.

“Do you not know that just as in the city squares old women wrangle, and in the courts lawyers argue, as in the brothels the pimps and in the taverns the drunks: so too philosophers contend in the schools, and poets think among the trees.” — Francesco Petrarca, Lettere disperse, ed. A. Pancheri (Parma, 1994), letter 40.

Petrarch wrote these lines to his friend Boccaccio in 1357. What would he have found in libraries? In his lifetime large libraries, such as the one here at the Vatican, had not been born. He imagined turning his book collection over to the Venetian state, but would he ever have studied there? Poets think amid the trees and in the woods.

There are no trees at the Vatican Library, literally speaking. To be sure there are trees of knowledge, supporting scholars in their climb up the arts and sciences. There are many branches and leaves of learning, allowing readers to get lost among the concentration of studies assembled in this place. But no trees, in the physical sense, and little vegetation at all, apart from the small courtyard outside the bar-café. Here the patches of green grass are divided by walkways and steps, where staff members gather on their breaks and a French friar puffs on his pipe. But scholars rarely loiter in this space; we cross quickly to the bar for our coffee or lunch, and then return to our books.

In the Vatican there are other trees. The Pinacoteca displays at least one image of the Franciscan arbor vitae, the Tree of Life that illustrates stages and reach of Christ’s life and sacrifice. A more famous representation is in Florence’s Accademia, by Pacino da Buonaguida.

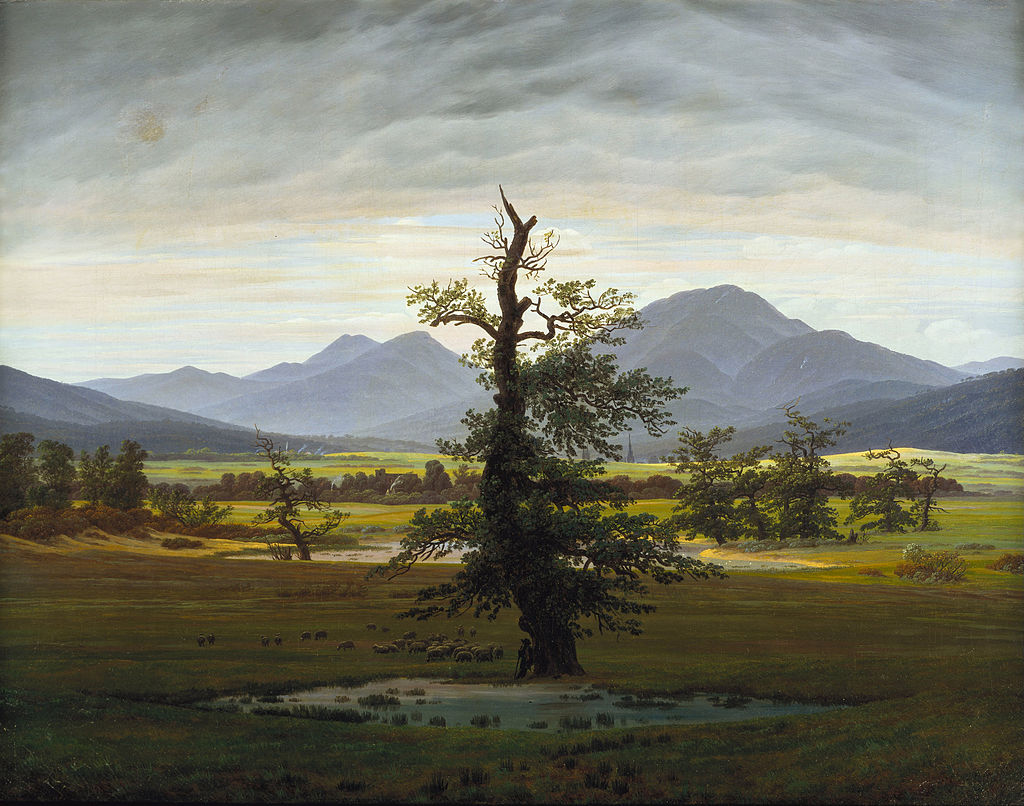

We can also consult books of symbols – I have here that of Cirlot – that identify trees as the world axis and the mediator between earth and sky, the world and heaven. In both cases, in image and symbol, we can take comfort in the larger meaning of trees, certainly beyond the loose, verbal sense of ‘treeing’ or connecting nodes into a larger network of phones or computers. This figure of speech, in its technological employ, seems to impoverish rather than enrich language, even as it hearkens to its deeper range of meaning.

But all these ways of thinking about trees – in image, in symbol, in technological utilitarian figure – do not move us a jot from the fact that there are no trees in the Vatican Library. Scholars converse among their manuscripts and printed books like the elders of Troy — “so droned and murmured these old leaders of the Trojans on the tower” — , with more circumspection and less passion than lawyers in the courts or pimps in the brothels.

But poets, Petrarch tells us, think amid the trees. And I recall a few lines from Yeats:

The trees are in their autumn beauty,

The woodland paths are dry,

Under the October twilight the water

Mirrors a still sky….1

He captures for us the cold air, the crackle of leaves, the hushed presence of swans on the lake, the color of the trees, still visible in the evening light. The autumn trees evoke his memories at the turn of the year. These trees show age: not just their age, but the revolving years of the poet, who observes the present and recalls the past in equal measure, so that observation and recall intersect, inform one another, and lend another meaning to the moment, aside from abstract speculation about image or symbol. Do we scholars do that? Or does not this poetic mood seem errant to us, impede our speculation and distract us from our scientific mission?

Small wonder, then, that the library has no trees. For in the poet’s world trees are not figurative abstractions, or biological entities subject to scientific analysis. Rather they are part of the poet’s environment, his very sensorium, in the sense that they speak to the poet about life and age, time and death: these are matters that, if we took them seriously, would disturb our research, and perhaps lead us to leave the library early.

Robert Frost in his woods imagined the trees talked to him, like something “that talks of going / But never gets away, / And that talks no less for knowing, / As it grows wiser and older, / That now it means to stay.”2 So the trees moved in their fixity and rootedness, not with a movement of place, but in a movement of time.

Leave A Comment