Freedom of thought in twelfth-century Paris: how Latin learning (and love) left us a legacy of creative inquiry

A good man asked the doctors of

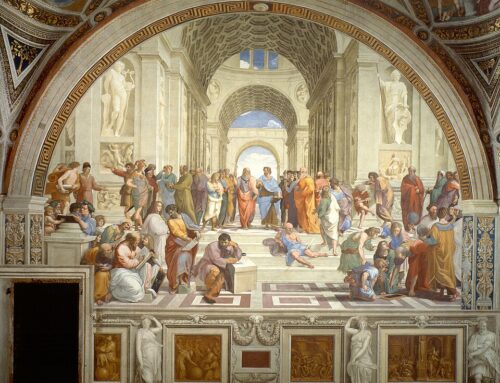

Abelard is the first of the new order: the scholar for scholarship’s sake. Patrimony and knighthood he left to a younger brother, recognising in himself a vocation for letters as some men might for religion: and though he died in such a fashion that Peter the Venerable writes of it with a sort of heartbroken passion of reverence, he knew it for the breaking of the proudest scholar in Europe. It is easy to belittle Abelard’s achievement, the depth and originality of his thinking, the harmony of his poetry, the quality of his prose. It remains that he is one of the makers of life, and perhaps the most powerful, in twelfth century Europe.… His tremendous weight flung into dialectic and philosophy did but incline a balance already swaying, for north of the Alps, in this as in the other Renaissance, the current always flows from pure humanism to speculative theology.

“O nightingale, give over

For an hour,

Till the heart sings,”

would have been written, even if Abelard had not come to neglect the schools for a windflower of seventeen growing in the shadow of Notre Dame, and set her lovely name to melodies lovelier still. But he stamped himself on the imagination of the century in a fashion beside which Petrarch’s influence on the sixteenth becomes the nice conduct of a clouded cane….

In the schools he kept his sword like a dancer: Goliath they called him with the club of Hercules, another Proteus, flashing from philosophy to poetry, from poetry to wild jesting: a scholar with the wit of a jongleur, and the graces of a grand seigneur. His personality, not less than his claim for reason against authority, was an enfranchisement of the human mind.

Helen Waddell, The Wandering Scholars of the Middle Ages

Leave A Comment