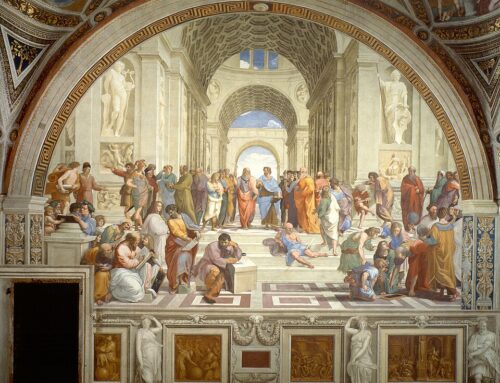

Professor Demos would use Plato and other great philosophers to demonstrate that proving any proposition to be true in the final and ultimate sense was impossible. His approach to critical thinking planted a seed in me that grew during my years at Harvard and throughout my life. The approach appealed to what was probably my natural but latent tendency toward questioning and skepticism.

I concluded that you can’t prove anything in absolute terms, from which I extrapolated that all significant decisions are about probabilities. Internalizing the core tenet of Professor Demos’s teaching — weighing risk and analyzing odds and trade-offs — was central to everything I did professionally in the decades ahead in finance and government….

I’m asked from time to time which undergraduate courses best prepared me for working at Goldman Sachs and in the government. People assume I’ll list courses in economics or finance, but I always answer that the key was Professor Demos’s philosophy course and the conversations about existentialism in coffee shops around campus. For me, embracing these two perspectives brought me a sense of calm in what were incredibly stressful situations.

There was a point in the early 1980s when the Goldman Sachs arbitrage department, which I led, lost more money in one month than it had made in almost any one year, driven by severe declines in the equity markets. Given the vicissitudes of markets, there was no way to tell whether we’d reached the nadir and recovery was around the corner — or whether we were about to go over a cliff. Despite the immense pressure, and the emotional state of the markets, I drew on an existential perspective, and my colleagues and I made careful, probabilistic decisions to adjust our portfolio, and we weathered the storm.

For other posts on the humanities and finance, see here and here

Leave A Comment