Upstream on the Cam: thoughts on advocacy for the humanities and other sports.

Editor’s note: the writer, Jerome Westgate, is an avid reader of the site and sent along this recent letter to a friend. I thought it worth printing in its entirety.

Dear Phil,

Thanks for your letter. It has been a long time. The town has changed even as the Cam has remained the same with its rowers and punters. I was rowing awhile yesterday and thought about how I could respond to your letter. I needed time to think, and on the river is a good place for it, away from the street noise. I rowed upstream from Baits Bite Lock to Jesus Green. Eliot called a river a strong brown god; rowing against the current lets me act out a metaphor of independence. Kidding aside, it also allows me to see everything glide by swept along by the current, and so the metaphor shifts my focus to what time carries along: trends, ideas, and faces.

Here the latest trend is advocacy. You won’t find anyone among the educated class who doesn’t speak as an advocate for something: it’s what’s done. You turn around in Newmarket Road or Bridge Street and hear advocates for political liberty, for housing, for the environment, for greater student authority, for science, and yes, sometimes even for the humanities. At least the advocates don’t need advocates!

At this point you’re probably recalling old Prof. Porterhouse, who smelled of tweed and talked at length about the Latin advoco: I call, invite, summon; console or recommend: though the advocatus might mean a supporter or friend of a person or cause. Latin lives, despite its untimely death, for we are clearly living in an age of advocacy. People want causes heard, supporters marshalled, parties formed. This has left folks like you and me out in the cold, or rowing our own little boats.

Do you remember Grantham? Big, thick-jawed, with the looming forehead, the loudest voice in the room, shouting down anyone who crossed him? I’m sure you do. We were both there when he took on all comers at The Eagle, so much so that Finnegan asked him to leave. Now that was a row! I’m reminded of him when I see these advocates. There’s no subtlety, humor, or self-awareness. What does it take to wake up on the world with an assurance that you are right and those who disagree are wrong?

What a strange world nowadays! All this self-righteous passion alongside the clinical technology. We are split in two, with neither side recognizing the other. It’s like the curse of the fall described by Aristophanes, except it’s not male split from female, but body from mind, left brain from right, with two sides carrying on as if each possessed the whole.

I know what you’re going to say: “it’s the two cultures all over again.” When Snow delivered the Rede Lecture – even before our time, remember – and Leavis responded with his vitriolic Richmond Lecture farewell (more like a swear and farewell), the stage was set for later generations: our own, and now the present. Never would the two sides find common ground again. At least Arnold spoke of “literature and science”; we now have the current “fuzzies and techies,” as if from a bad science fiction novel. I found again Leavis’s words: “Snow’s relation to the age is … characterized not by insight and spiritual energy, but by blindness, unconsciousness, and automatism.” Turning Snow into a machine (a snow blower?), Leavis reduces the man’s argument to the terms of 1950s artificial intelligence (I speak not pejoratively: for then there may have been more intelligence than artifice, whereas today the ratio is reversed). Snow is de-humanized – we might now say trans-humanized – and as such is as far from Leavis’s ‘humanism’ as one could imagine. But only to a point. Leavis had odd Downing College humanism: he argues with everyone, from literary sophisticates to industrial scientists. His advocacy for literature is so famously narrow that literary critics have been pained to find it.

But he was the today’s advocates’ exemplar. The variety of advocacy, but not its breadth, has grown in the last fifty years. In our raw youth, we could not have imagined the causes celebrated today. But our vision is not much brighter now, either. If the causes are more numerous, they are more limited. For the point above all is to be an advocate, and defend your plot of ground for all its worth by attacking the ignorance and viciousness of the adversary.

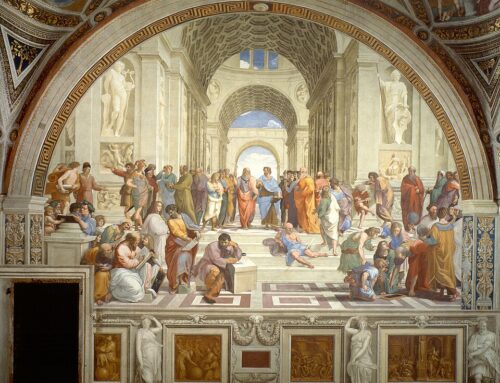

What a difference between Leavis and the poet for whom he wished to advocate! The difference in discourse, in respect, in introspection and inwardness – genuine learning – shows the difference in the times. When Arnold delivered his Rede Lecture in the 1880s, he spoke of the overlap and common ground of the humanities and the sciences; for the study of literature could be scientific, and literature itself includes scientific discussion – Copernicus, Galileo, Darwin. We could now include Chargaff, Szent-Györgi, and Edgar Mitchell. Nonetheless Arnold argued that literature includes a feeling for beauty and a higher moral purpose, beyond any immediate demands for usefulness. Here he foreshadowed, or reached out to, thinkers like Tagore and Kakuzo.

But that’s the problem with modern advocacy, isn’t it? There is little historical depth dimension and less inwardness, which would foster, as it did for Arnold, a deeper sense of both humility and certainty. Did you read the recent report from the Nuffield Council on Bioethics? It represented a stance of what I call ‘mild advocacy’: circumspect, seeming to listen to both sides: as if there were only two with regard to the ethics of genetically manipulating human beings – no, wait, human “embryos.” On first reading it appeared to avoid taking a stand on the question, and instead set out numerous guidelines, whose terms – “the welfare of the future person”; “solidarity”; “social justice”; and “disadvantage” – beg the question of what they actually mean! But the graver problem, as I see it, is that it failed to discuss in any meaningful way the ethical principles that genetic manipulation engages. What is the ethical good? Virtue (which ones?), pleasure, utility, happiness? How does one realize it? These questions have been debated over the millennia, and find the faintest echo in the report. Its writers seem serious: they write with a serious tone, with the best impersonal bureaucratic jargon – and these are the hallmarks of a serious thinker today, a thinker devoid of personality, or better a collection of thinkers, who can elide their views with one another – which is to say, each has no view and is essentially unserious, and not a thinker at all. Here the gentle and strident advocates are on common ground, for both employ catch phrases, “talking points,” in order to display the pretense of thinking without having to think for themselves.

I am about the point to disembark, and will write down these thoughts at The Orchard, where I can reminisce about old times. It occurs to me that I have rowed upstream also in face of the future, as it carries itself toward us incessantly. I remember how we could play with metaphors and bat them back and forth almost without end, as if in a fifth set at Wimbledon. There are no tiebreakers, thankfully!

Write again – we’ll begin where we left off.

Leave A Comment