Humanities and wholeness: reflections on Humanities Watch’s third anniversary

The site has grown a year older, along with its readers. Those devoted to its cause have read observations, articles, and quotes on artificial intelligence (AI), medicine, and the technical world in general.

Each of these subjects has its own partiality, its own peculiar tendencies and bias. The title of this observation concerns wholeness, the larger unity: each partial light, like phases of the moon, brightens only a limited space on the larger body of knowledge, leaving the remainder in shadow. With the end of another year, it is not too fanciful to consider the humanities’ place in fostering a sense of wholeness to the various lights of AI, medicine, and technology.

AI makes use of algorithms or mathematical formulae that design predictive patterns. They show us the answers of Alexa or our network of internet “friends”; they help determine the composition of pharmaceuticals and judicial sentencing. Robotic helpmates and even artistic portraiture now run with its programming, not to mention self-driving cars. AI possesses an obvious utilitarian function, even as, with these last two examples, it enters into the sphere of our social and cultural world. AI increasingly structures our physical lives, providing more sophisticated information and guidance. But how whole is this information? Ethicists have stressed the distinction between informed and knowledgeable AI, citing examples of the ways incomplete or partial data lead to skewed conclusions about the world in which we live and the decisions we should take. This is only the most obvious sign and symptom of its partiality.

Medicine also makes use of AI. More basically, our medicine diagnoses and treats our ageing bodies, combating viruses, repairing tissues and organs, waging war against the scourges of cancer and dementia. The incisiveness of conventional medicine lies in the objectified doctor-patient relationship, with physicians training their medical gaze on the embattled health of their clients and studying the bodies’ responses to their arsenal of potential cures. Yet again, we might ask, how complete is this approach, especially in its apparent objectivity, and whether an ‘objective’ medical assessment contains inherent limitations as well, for example in its reluctance to listen to patients’ narratives of their condition?

Technology is the watchword of these two domains, AI and medicine. We may be tempted to think of technology as the universal in our lives, and thus as less partial than the rest. But it is even more partial, especially when we imagine it as impartial, for here we limit our imagination and thinking and do not inquire about our own degree of understanding. We may imagine technology as useful, purposeful, and leave it as that. But here too this leaving shows our lack of energy, initiative, and curiosity, and our retreat before the possibilities of imagination. It lays a lazy emphasis on utility, utility defined by the parameters of technology.

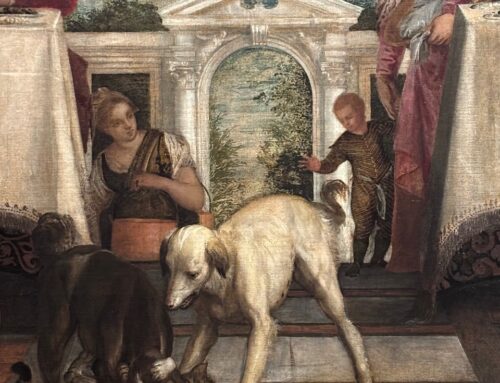

For does the nature of technology exhaust itself in its usefulness or practicality? We say that an artist uses technique: he or she also takes hold of specific technologies, for example laser engraving or photography, to bring art into view and foster a deeper understanding life’s truth. Here the artist points us to the higher and deeper purpose of technology: of disclosing what we normally do not see or imagine, or do not wish to see. This pointing is not typically understood as useful or practical. On the contrary, it can threaten our complacencies and conventions founded on a sense of useful practicality. Eugène Atget took photos of spring gardens in winter, such as the Jardin des Tuilieries;

Atget, “Spring” in Jardin des Tuilieries, 1907

Weegee recorded nonchalance during a ship fire in the East River;

Weegee, [Ship fire, New York Harbor]

and Garry Winogrand captured the informal spontaneity of New York’s light and shade.

Garry Winogrand, Untitled, from Women are Beautiful series

Each of these artists ‘knew his craft,’ but with a knowledge that transcended any deliberative calculation of what society found useful.

By the artistic vision that takes hold of technology I therefore do not mean what was come to be known as “virtual reality.” Though the virtual reality devices may also require art and imagination, they too may blind us to a deeper vision of life’s potential, especially when we rely on them as the source of this insight. Artists do not depend on tools in this sense. They may invent them, in the way that Brunelleschi designed the pulleys to build the dome in Florence. The tools serve the higher, creative purpose; technology is not the prize or the goal. The great humanist artist Leon Battista Alberti commemorated Brunelleschi’s achievement with the words, “Who could ever be hard or envious enough to fail to praise Pippo the architect [i.e., Brunelleschi] on seeing here such a large structure, rising above the skies, ample to cover with its shadow all of the Tuscan people, and constructed without the aid of centering or great quantity of wood?” 1

Brunelleschi, Dome on Santa Maria del Fiore, Florence

No Renaissance artist or thinker knew the advances of technology better than Leonardo da Vinci, yet his expertise brought him to ponder in his notebooks the human capacity for violence and destruction, and to employ literary images and symbols to express his philosophical insights in the age of Machiavelli.

The humanities help us shear away the barriers between and within ourselves, and so tap into our greater potential that our partial imaginings conceal from us. The commonplace function of technology may be to use machine power to enhance our lives. This function is good, though of course also harnessed for harm. The humanities show this function as partial in the larger sphere of our humanity. To say that humanity must drive or steer technology is also to remain driven by functional, therefore partial thinking. It is sleight-of-hand: we claim to control that which we fear controls us. We remain focused on control, rather than on creation, which moves in the larger realm, the realm of wholeness.

So AI, medicine, and technology allow the shadow side of our world to remain. In fact they divert us from it: but in this diversion they also remind us of the greater way, the way that humanity in its wholeness may be seen and realized. They show the future by preserving the past, even if this past appears more deeply obscured by shadow and estranged from our current concerns.

Of course practitioners of the humanities are often as partial or one-sided as those invested in the domains of AI, medicine, and healthcare. The partiality of the two cultures is alive and well. We aim to speak of the humanities in their full potential. Those genuinely devoted to the humanities, who travel its roads of inquiry, are experienced in its elliptical, often eccentric pathways, and these are the pathways that lead us within ourselves and well as out into the world with greater vision.

1. Leon Battista Alberti, On Painting, trans. J.R. Spencer, p. 40.

Leave A Comment