Humanities enhance business and STEM: an interview with Michael Tworek of Cambridge Humanities Group

Dr. Michael Tworek is the founder and CEO of Cambridge Humanities Group, an organization devoted to providing humanities insights and skills to business and STEM professionals. Dr. Tworek completed his Ph.D. in Renaissance history at Harvard University, where he began his consulting work with local and international companies. He recently sat down with Humanities Watch for this interview.

Humanities Watch: How did you come upon the idea of the Cambridge Humanities Group?

Michael Tworek: Two experiences in consulting inspired me to undertake this venture. First, I did some educational consulting while I was a lecturer in History and Literature at Harvard. This consulting in the Boston and Cambridge area showed me that the technologists involved in education who hired me were not very interested in content and pedagogy, even though these areas provided both the clients and me great satisfaction. I found it ironic that vendors in ed tech did not appreciate the value of content and teaching.

My second experience was in management consulting. My friends at the top firms like BCG and McKinsey and Co. realized that my humanities and history background made me creative and skilled in ways that others with a STEM background were not. For example, I advised a company that was weighing an investment in Catalonia and helped them consider the history and culture of the area, including the separatist tendencies.

These experiences led me to create a company that stressed content and pedagogy, along framing the larger questions that face professionals in STEM and other fields.

HW: What do you consider its mission? How does it dovetail with your experiences in the humanities (and business world)?

MT: It’s very straightforward: to offer humanized education for the 21stcentury. This education entails acquiring skills and perspectives not just for your first job, but for the rest of your life. Among these are the soft skills in humanities and social science, skills that allow us to interact with others and human society as whole. They include the “7 Cs”, modeled on the original seven liberal arts: critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and creativity, along with higher-level skills in curiosity, compassion, and competence.

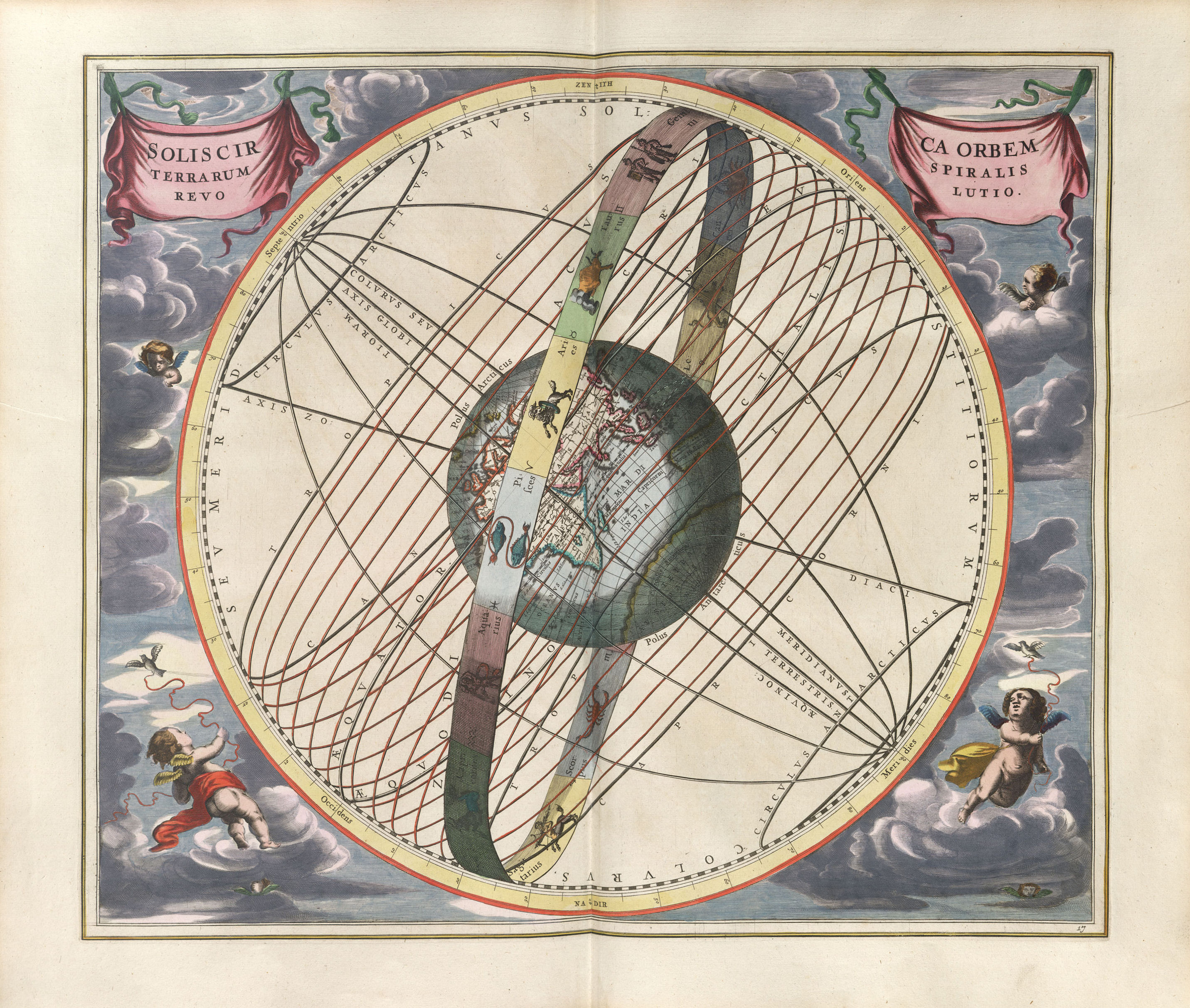

This mission dovetails with my research on Renaissance humanism and early modern world. For example, the printing press changed the world as people knew it, yet this technology did not eliminate the humanities. On the contrary, the printing press enriched and enhanced the importance of humanities to the elites and the socially mobile, because the humanities proved so adaptable to professional and personal needs. AI may make coding irrelevant to most of us, but will not make the essential skills of the humanities irrelevant. They will never go out of style or out of date.

HW: Why do your clients find appealing an humanities approach to business and technology?

MT: We help them to re-think their approach to business and STEM problems, through the examples from the humanities, including literature and history. This approach is opposed to more static business models that are less capable of adapting to their current situation. The humanities approach helps them solve their problems, learn something new, and also have fun doing it.

One example comes to mind. When consulting with Chinese executives, I discussed the invention of the printing press. We associated the European invention with the Chinese invention of printing that occurred much earlier, and explored the disparate impacts. We thought through the unintended consequences of technology in different cultures, and then through the problems these executives were facing today in their own companies and hierarchies.

HW: What do you consider the biggest deficits in current business school or engineering programs?

MT: In a nutshell, teaching the soft skills: the 4 Cs (critical thinking, creativity, collaboration and communication) along with higher order skills: curiosity, compassion, competence. That is what we find missing. There are scientists and engineers who have of course a tremendous capacity for soft skills, but these skills are often seen as an afterthought or learned haphazardly. Here is an opportunity to incorporate the humanities in these programs, since the humanities are the cradle of soft skills. The leaders in business and STEM fields, we should remember, were also deeply engaged in the humanities: the Medici, Einstein, not to mention Steve Jobs, who was a humanities major. We can thank the humanities that we have the iPhone. This is often overlooked. The two – humanities and STEM – are complementary in many ways.

HW: In the same measure, how would you advise humanities programs to change their current educational programs?

MT: There are several ways, based first on my experiences at Harvard and then afterward.

First of all, we should teach graduates of humanities programs to be better public speakers and communicators. We can show the power of rhetoric and persuasion to communicate ideas from the humanities and in other fields.

Second, there should be greater training in statistics and numeracy, and more broadly STEM fields. Humanists can communicate better with STEM people across the “divide” and improve the interaction between fields. One example is in digital humanities. Third, we need to connect the value of transferable skills to concrete employment opportunities. We must consider how soft skills are indispensable to work and to our society as a whole. More directly, there should be course options, such as digital labs or mini-labs that connect the humanities to real world problems and opportunities, such as entrepreneurship.

Finally, the public humanities are a way to have a discussion about how we can enjoy the humanities for their own sake; STEAM too is a way of understanding STEM subjects through the arts. Of course, we need to think about who becomes engaged in STEAM: not just STEM students but also artists and those in the humanities. Another program that we are developing at Cambridge Humanities Group is STEMLA: STEM plus liberal arts, that brings them together in an integrated way. This shows again the value of the liberal arts in STEM. Public humanities can take a self-reflective turn, for example in highlighting how the liberal arts are a national treasure for the US and beyond.

HW: What general advice do you give students majoring in the humanities? In business and STEM?

MT: My academic position as a teacher and advisor also gives me reason to consider this question. First, don’t undersell the value of your humanities degree to employers, families and friends. 86 percent of employers complain that new college graduates are not prepared for the work they face, no matter their major!

Second, humanists should emphasize and develop what we do well: reading, writing, thinking creatively, “thinking fast and slow,” to use psychologist Daniel Kahneman’s phrase. These transferable skills are needed in every environment, STEM and non-STEM. Employers are looking for them.

Last but not least, don’t be afraid of STEM. Bring your curiosity to these fields: be conversant with these fields of knowledge, and discover the ways your skills relate to these fields.

With respect to business and STEM students, I’ve advised many of them, and many are amazing humanists. My basic advice is to take humanities courses: their content is a cradle of creativity and new ideas, new perspectives and images. The most successful students in these fields do not shy away from these courses.

Second, I would stress again the importance of learning the arts of persuasion: too often these students do not consider human factors when presenting their point of view. Humanities teach us empathy and compassion for others, who may not initially share our point of view.

Leave A Comment