The long history of the humanities crisis: a crisis both chronic and acute. From the article:

Rankings-hungry universities across the country tout their STEM programs and their connections to internships and industry. Helping themselves to trendy tech buzzwords, they brand themselves as centers of innovation that drive economic growth and offer students salvation from the robot apocalypse. Academics in the humanities and social sciences, who have seen the collapse of their job markets despite steady demand for their teaching, generally feel the modern university to be in crisis, often struggling to articulate what exactly has happened to their place in the world.

Two new books try to explain how we ended up here. In Nothing Succeeds Like Failure, Steven Conn suggests that it was the rise of the business school, and the spread of its values through the university more broadly, that started this process of transformation. Ethan Schrum’s The Instrumental University takes a wider view, describing a movement among influential university leaders after World War II to make the research university an engine of knowledge for economic development and other dimensions of “national purpose,” breaking with the university’s traditional values of truth-seeking….

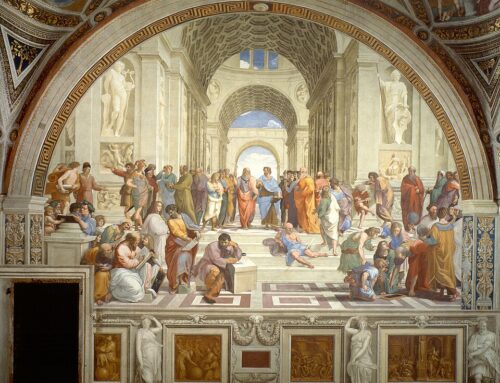

America’s first business schools, known in the nineteenth century as “commercial colleges,” provided to young men employed in industry the sort of formation that more traditional higher education, more appropriate for lawyers or doctors, did not. Because of their practicality and egalitarianism, commercial colleges often hosted a spirit of rebellion against the elitism and stodgy classicism of academia. Industrialists, flush with wealth from late–nineteenth-century transformation of the American economy, were acutely aware of the commercial colleges’ lack of social capital, and they pushed to establish business in elite universities in order to make the businessman a socially respectable figure….

“By the turn of the twenty-first century,” Conn writes, “business school education had aligned itself with the demands of business more than at any time since Wharton began offering classes in 1881.” Business schools finally stopped trying to prove they had rigorous intellectual standards and were a social good, because the money they brought in—and universities’ increasing adaptation of managerial ideas in their own time of neoliberal crisis—spoke for itself. Running universities like corporations, forcing academic departments to justify their existence, and appropriating resources on the basis of “productivity” and “value-added” all brought academic administration and business school ideas into closer sync….

In the 1950s and 1960s, [university administrators] frequently wrote of transforming the university into an “instrument” of social change, of “using” it to solve pressing problems. Universities would produce technical knowledge for economic development, urban planning, and industrial relations. Schrum calls this vision the “instrumental university.” The ideal was an unapologetically technocratic adaptation of the earlier progressive impulse: The university’s goal was to provide the knowledge and the people who could, in Clark Kerr’s phrase, “administer the present.”

The visionaries of the instrumental university subscribed to a form of American exceptionalism that historians call “American modernity”—a widespread belief among American elites, invigorated by triumph in World War II, that the scientific and technological might of the United States made it the exemplary modern nation with a mission to serve as a model for the world….

In becoming instrumental, Schrum writes, the postwar university “lost some of what made it special. It became more like other large institutions, caught up in the economics and politics of the day, rather than a place intentionally set apart from those currents so that scholars could pursue truth.”

For other posts on the humanities crisis, see here.

Leave A Comment