Life at a distance: thoughts on the internet and (self-)isolation. From the article:

It is beyond debate that these remote collaborations may be less fruitful than in-person meetings; the learning less effective than what we absorb in hands-on environments; and the socializing markedly less satisfying than the alchemy of face-to-face connections. Even staunch advocates of remote work such as Jason Fried, author of the book “Remote,” have acknowledged that it is important to occasionally get your team together in person to cement social bonds, build trust and brainstorm.

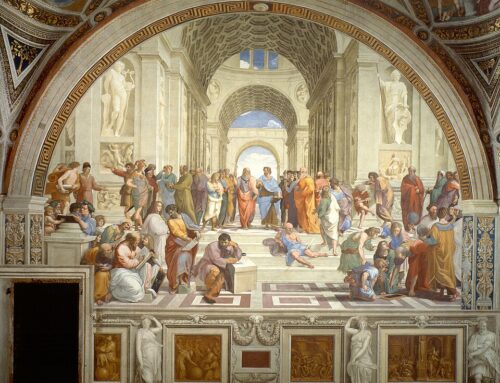

But why these online-only connections don’t quite cut it remains something of a mystery to social scientists. Sure, it is easy to say that humans evolved for in-person communication, that our uniquely expressive faces, eyes, bodies and vocal cords convey far more information than words on a screen ever could. And all this isn’t only self-evident but backed by a fascinating array of research: Anthropologist Ray Birdwhistell has asserted we are capable of 250,000 different facial expressions. Research by body-language experts Allan and Barbara Pease indicates that 60% to 80% of the impact of someone’s arguments in a negotiation is attributable to body language.

Operating under the assumption that capturing more of this nonverbal communication is always better, psychologists have created a measure of how rich a medium is, which they call “social presence.” Video chat has a high level of social presence, while texting has a low one.

But for anyone who has ever been reassured by a text from a friend, laughed at a colleague’s joke in Slack or had their mind changed by an exchange on social media (the rarest scenario of them all), it is clear that the richness of a medium isn’t the sole determinant of how it makes us feel.

Even a communication with a high level of social presence can’t be depended upon to cure the gnawing hunger for human connection that bares its yellowed fangs when we least expect it. Who among us hasn’t logged into a Skype, Zoom, Google Hangout, WhatsApp or [insert your service of choice here] video call, gazed upon a screen full of other people on their laptops and felt, if only for a moment, that flickering existential dread? “This is how I will die—alone and under less-than-flattering light.”

In an age of remote everything, especially one in which our jailer is a potentially lethal virus, the underlying feeling is that how we choose to live our days is how we will end them: hunched over a screen, pressing “refresh” until the very end….

If the richness (or lack) of a medium can’t explain why the quest for connection on the internet can be so fruitless, perhaps another, older theory does.

In 1956, sociologists Donald Horton and Richard Wohl coined the phrase “parasocial interaction.” It characterized the emotional ties millions of people had developed with performers and personalities beamed into their homes through the then-new medium of television….

The internet also creates a mental equivalence between everything and everyone on a given network, one that erases the boundaries between our interpersonal relationships and parasocial ones. When friends’ tweets, TikToks and Instagram posts are interspersed with content created by professionals we don’t know, selected for us by an automated filter, we perform the mental trick of viewing all of it as the same sort of thing….

The antidote to the slow poison of parasocialization is, of course, socialization. Just like our primate ancestors. Live and in the flesh. And unfortunately, millions of us are about to find out just how long we can survive without it.

For other posts on loneliness in the age of the internet, see here.

Leave A Comment