Historians have long argued that the value of their field lay in its applicability to the present day. It serves society best, according to a recent formulation, as a guide that encourages broad perspective and careful judgement among policy makers in the public sphere.

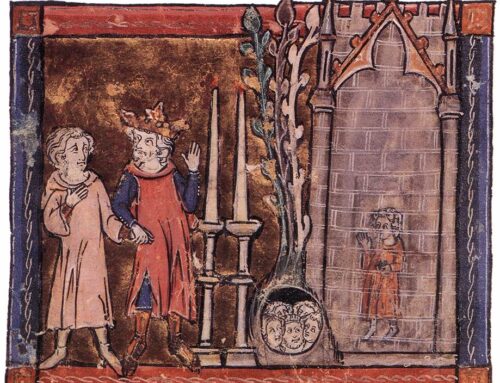

The judgments appear particularly appropriate now, as the world endures a pandemic that has evoked images of prior catastrophes dating back to ancient and medieval times. The Black Death (1348) of the fourteenth century, the subject and era that I study, has had a special place in current discussions in light of dramatic scenes from Italy of citizens singing from rooftops and reaching out to each other on social media, following the spirit of Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, written in Florence during the medieval contagion, depicting self-quarantined protagonists passing time, “sheltered in place,” telling stories to each other as the plague raged around them. That Boccaccio’s upper-class brigata removed themselves from the city to a country estate brings to mind well-to-do New Yorkers, who have left their own city for safety in the suburbs. But the examples of Boccaccio, Florence and the Black Death more generally have too often been appropriated in simplistic ways in journalistic pieces that offer easily digested nuggets of information. A recent essay in The Economist (“Throughout History, Pandemics Have Had Profound Economic Effects: Long Term Effects Are Not Always Dreadful,” March 2020) put the issue starkly from an economic perspective: the Black Death brought greater integration of markets, a rise in wages of laboring classes and a general Schumpeterian “creative destruction” that gave rise to the Renaissance and even created the preconditions for the economic rise of the modern Western world.

It is important for pundits take a collective step back, think through historical parallels carefully and avoid the teleology inherent in looking backward and the concomitant impulse to wrap the past in a neat attractive package. History is best understood in context, with all its attendant contradictions and concurrent trends. The emphasis on the economic “long term” amid the human suffering of the pandemic raises questions about the moral compass of devotees of classical economics and recalls the famous quote attributed to John Maynard Keynes that “in the long run we are all dead”– a statement that is perhaps more applicable today than ever.

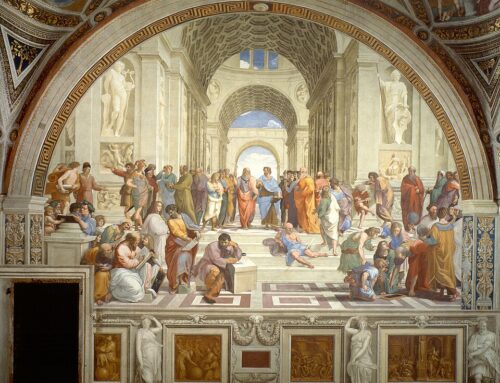

The economic consequences of the Black Death have been the subject of a robust and nuanced academic discourse for more than a generation. Scholars have argued that plague caused a “cessation of activities,” notably in trade and commerce, that set off widespread depression. They explain the Renaissance that followed as the result of investment in “culture” rather than in unprofitable businesses. Others have argued that rising wages of the laboring classes, along with changes in the structure of wealth, created “permissive” economic circumstances that encouraged luxury consumption and ostentation that was emblematic of the Renaissance, particularly in Boccaccio’s Florence. Still others detach altogether the cultural achievements of the Renaissance from economic developments, and question historical periodization itself.

In any case–and the example of Boccaccio notwithstanding–fourteenth-century “policy makers” understood little about social distancing and shelter in place, and if there was a “cessation of activities” it resulted from the mortality itself and the massive death toll that has been estimated at one-third to one-half of Europe. A most striking pattern during the medieval pandemic was a sharp increase in violence: both within cities/states and among them. The uptick is counter intuitive, as it helped spread the disease, and is not part of the calculus of economic histories or current appropriations of them. And yet the roots of violence lay in the basic structure of medieval/Renaissance society, with its social and economic stratification and the existence of a landed aristocracy, whose income depended on property, which declined in value as a result of the contagion. This encouraged the men, whose raison d’être was warfare, to sell their services as mercenaries to recoup their losses, creating a key feature of the period treated independently and famously by Niccolò Machiavelli, who condemned mercenaries as a feature of the “moral cowardice” and decline of his native Italy, and by Jacob Burckhardt, who saw in the men the apotheosis of the individualistic “Renaissance” figure that gave birth to “modern” politics. Meanwhile, deep-rooted inequalities and shifting economic circumstances stoked urban violence, which connected over to external warfare through large numbers of political exiles, who joined bands of free roaming mercenaries in the hope of using them to destabilize further the political situation at home. Indeed, a close look at Boccaccio’s own life and career reveal his deep connection to Florence’s domestic discord and military activities, including a war promoted in 1349-50 by his close friend Francis Petrarch, the erstwhile “prince of peace.” Violence and warfare had their own economic consequences that still need be inserted into discussions of the economy of the plague era.

The social and economic structure of today differs from that of the fourteenth century. But as I write, violence has engulfed American cities and there are ominous signs of discord in the international arena. The degree to which these developments owe to the pandemic, to concurrent trends, or a combination of two, represent the type of nuanced questions that those who appropriate the past must ask in order to understand the present. What seems right now the most palpable point of convergence between the past and the present is the awareness of the precarious nature of human existence.

William Caferro is Gertrude Conway Vanderbilt Professor of History and of Classics and Mediterranean Studies at Vanderbilt University. His most recent book is Petrarch’s War: Florence and the Black Death in Context.

For other posts on plague and modern society, see here.

Leave A Comment