Measuring gain and counting loss: recalling the history of Hindu-Arabic numerals. From the article:

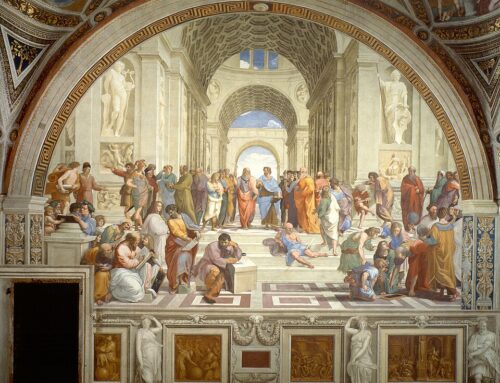

Founded as a private collection for caliph Harun Al-Rashid in the late 8th Century then converted to a public academy some 30 years later, the House of Wisdom appears to have pulled scientists from all over the world towards Baghdad, drawn as they were by the city’s vibrant intellectual curiosity and freedom of expression (Muslim, Jewish and Christian scholars were all allowed to study there).

An archive as formidable in size as the present-day British Library in London or the Bibliothèque Nationale of Paris, the House of Wisdom eventually became an unrivalled centre for the study of humanities and sciences, including mathematics, astronomy, medicine, chemistry, geography, philosophy, literature and the arts – as well as some more dubious subjects such as alchemy and astrology….

[T]he academy ushered in a cultural Renaissance that would entirely alter the course of mathematics.

The House of Wisdom was destroyed in the Mongol Siege of Baghdad in 1258 (according to legend, so many manuscripts were tossed into the River Tigris that its waters turned black from ink), but the discoveries made there introduced a powerful, abstract mathematical language that would later be adopted by the Islamic empire, Europe, and ultimately, the entire world….

Tracing the House of Wisdom’s mathematical legacy involves a bit of time travel back to the future, as it were. For hundreds of years until the ebb of the Italian Renaissance, one name was synonymous with mathematics in Europe: Leonardo da Pisa, known posthumously as Fibonacci. Born in Pisa in 1170, the Italian mathematician received his primary instruction in Bugia, a trading enclave located on the Barbary coast of Africa (coastal North Africa). In his early 20s, Fibonacci traveled to the Middle East, captivated by ideas that had come west from India through Persia. When he returned to Italy, Fibonacci published Liber Abbaci, one of the first Western works to describe the Hindu-Arabic numeric system….

“Those who wish to know the art of calculating, its subtleties and ingenuities, must know computing with hand figures,” Fibonacci wrote in the first chapter of his encyclopedic work, referring to the digits that children now learn in school. “With these nine figures and the sign 0, called zephyr, any number whatsoever is written.” Suddenly, mathematics was available to all in a useable form.

Fibonacci’s great genius was not just his creativity as a mathematician, however, but his keen understanding of the advantages known to Muslim scientists for centuries: their calculating formulas, their decimal place system, their algebra. In fact, Liber Abbaci relied almost exclusively on the algorithms of 9th-Century mathematician Al-Khwarizmi. His revolutionary treatise presented, for the first time, a systematic way of solving quadratic equations. Because of his discoveries in the field, Al-Khwarizmi is often referred to as the father of algebra – a word we owe to him, from the Arabic al-jabr, “the restoring of broken parts”—and in 821 he was appointed astronomer and head librarian of the House of Wisdom.

Leave A Comment