Finding Merlin: new technology uncovers new clues about the magus. From the article:

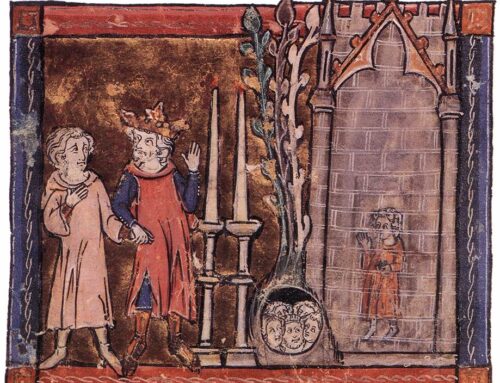

Medieval manuscript fragments discovered in Bristol that tell part of the story of Merlin the magician, one of the most famous characters from Arthurian legend, have been identified by academics from the Universities of Bristol and Durham as some of the earliest surviving examples of that section of the narrative.

The analysis also uncovered how the hand-written documents ended up in Bristol, differences in the text from previous versions of the story and by using multi-spectral imaging technology, the researchers were able to read damaged sections of the text unseen by the naked eye and could even identify the type of ink that was used….

The fragments contain a passage from the Old French sequence of texts known as the Vulgate Cycle or Lancelot-Grail Cycle, which dates to the early 13th century. Parts of this Cycle may have been used by Sir Thomas Malory (1415-1471) as a source for his Le Morte Darthur (first printed in 1485 by William Caxton) which is itself the main source text for many modern retellings of the Arthurian legend in English….

Professor [Leah] Tether said: “We were able to date the manuscript from which the fragments were taken to 1250-1275 through a palaeographic (handwriting) analysis, and located it to northern, possibly north-eastern, France through a linguistic study.

“The text itself (the Suite Vulgate du Merlin) was written in about 1220-1225, so this puts the Bristol manuscript within a generation of the narrative’s original authorship….

“Working with Professor Andy Beeby of Durham University’s Department of Chemistry was also a game changer for our project thanks to the mobile Raman spectrometer developed by him and his team, Team Pigment, especially for manuscript study. We captured images of damaged sections and, through digital processing, could read some parts of the text more clearly.

“This process also helped us to establish, since the text appeared dark under infra-red light, that the two scribes had in fact used a carbon-based ink – made from soot and called ‘lampblack’ – rather than the more common ‘iron-gall ink’, made from gallnuts, which would appear light under infra-red illumination. The reason for the scribes’ ink choice may have to do with what particular ink-making materials were available near their workshop.”…

In addition, the team found that the Bristol fragments contain evidence of subtle, but significant, differences from the narrative of the stories found in modern editions.

There were longer, more detailed descriptions of the actions of various characters in certain sections – particularly in relation to battle action. One example of this is where Merlin gives instructions for who will lead each of the four divisions of Arthur’s forces, the characters responsible for each division are different from the better-known version of the narrative….

Professor Tether added: “Besides the exciting conclusions, one thing that undertaking this study, edition, and translation of the Bristol Merlin has revealed is the immeasurable value of interdisciplinary and trans-institutional collaboration, which in our case has forged a holistic, comprehensive model for studying medieval manuscript fragments that we hope will inform and encourage future work in the field.“

For additional reporting on this story, see here, here, and here.

h/t G. Heath King

From the University of Bristol webpage article: “Merlin has been strategising the best plan of attack. There follows a long description of the battle. At one point, Arthur’s forces look beleaguered but a speech from Merlin urging them to avoid cowardice leads them to fight again, and Merlin leads the charge using Sir Kay’s special dragon standard that Merlin had gifted to Arthur, which breathes real fire.” We could use a bit of that fire…maybe this ‘resurfacing’ of Merlin is timely?