Jousting with Judgmentalists: that certainty can precede calamity, as written at Delphi

A hard time we had of it, crossing the southern hills. Sir Felix marshalled us together and encouraged us to maintain our spirits. The obstacles to our journey had seemed to grow and in direct relation to our feelings of weakness, but Felix reminded us that our curiosity and our studies would see us through.

Our trespass on to the plain brought relief mixed with alarm. The terrain was flat, but also barren. The vegetation appeared unable to flourish in the fertile soil, as it was constantly cut off from bearing fruit. The reason for this became clear, for we saw laborers pruning the plants as they first rose from the dirt. Their pickings might be small, they told us, but at least – this was the goal – their harvest always produced equal measure. The local clergy, they said, had introduced this practice and there was no deviating from it. This clergy only recently gained command in the region. They intimidated the workers with their proclamations of superiority and their general haughtiness. They both preached and bore weapons, like the Templars or Mamluk sultans of old.

“Look,” cried one, “here they come!” And in the distance, we saw a legion of knights kicking up the dust as they speedily advanced on us. Each was mounted on a horse of enormous size, high off the ground, which added another degree of haughtiness to their scowling faces.

“Who are you? Where do you come from?” demanded the foremost among them. He had armor that puffed out his chest and wore a helmet with a large J affixed to it in silver and gold. He held a staff in one hand and a sword in the other.

“I am Sir Felix of the Alchemical Adventurers,” our leader said. “These are my friends, and we are traveling the world and exploring the mysteries of knowledge. We ask ourselves, like Odysseus, “What kind of land have we come to now? Are the natives wild and lawless savages, or hospitable folk who welcome strangers?” [cf. Books 6 and 9].

“You have come unhappily here, Felix,” said the head clerk. “You speak of alchemy, and alchemy is not needed or wanted here. Nor this talk of mysteries, or Greek epic. You and your ilk are hopelessly benighted and old-fashioned.”

“If you meant be-knighted,” Felix replied, “I thank you for this courtesy. But what could be old-fashioned about seeking knowledge?”

“We have found knowledge!” thundered the clerk. “We do not seek it. And your premises about seeking knowledge, using the privileges of the pseudo-science alchemy, evince to us that you want to preserve and advance these privileges, when the world here is better shaped by our equitable certainties. Be off!”

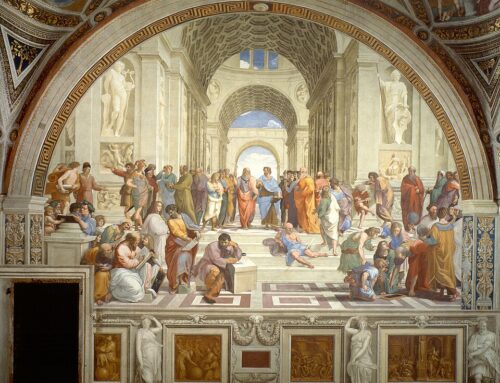

“Alchemy is as much art and metaphor as a science. We gather a sense of our ignorance and our knowledge through a symbolic process. We mine the past in order to round out our sense of who we are, even as we devote ourselves to experimental inquiry. As we take to heart, an unexamined life is not worth living.”

“Nonsense, and more Greek nonsense, too! Do you think to fool us? These approaches are designed only to maintain your position, and are a disguise for your secret desire to hold power. How devious you are, you and your little friends, while you pretend to be unenlightened!”

At this point the youngest among us, Puck, spoke up. Puck had joined us only a few years ago, after our tour of nuraghes of Sardinia. “Why,” he asked the cleric,” do you have a large J on your forehead?”

The cleric’s face grew redder. “How ignorant you may actually be,” he said. “We belong to the Order of Judgmentalists. We are the fastest growing order among the orthodox. To us belong armies of scholars, bureaucrats, and scientists. I am in this region the Chief Judgmentalist, Sir Richard the Proud-Hearted. But we are a global force, with followers everywhere.”

Sir Felix smiled and started singing,

Arma virumque cano, Troiae qu primus ab oris

Italiam fato profugus Laviniaque venit

litora….

[I sing of arms and of a man: his fate

had made him fugitive; he was the first

to journey from the coasts of Troy as far

as Italy and the Lavinian shores. Mandelbaum trans.]

“What strange language is this, what incantation?” roared the cleric.

“No incantation,” Felix said, “but Virgil’s Latin. The book was a gift to me by Father Welte, after he returned from the battlefields of last great war. It is work of timeless insight.”

“Not at all: a vestige of the past, no longer wanted.”

“Why not?”

“Latin was the language of oppressors, imperialists, and should be banned from the schools, unless among a select few, whose lives are otherwise useless ones to humankind.”

“You would only speak English, then?”

“Of course! It is all one needs to decry the injustice of the past and announce to people a more perfect and equal present. Yet we allow for Spanish, Arabic, or Mandarin, too, as languages to circumnavigate the globe.”

“The four linguistic horsemen, then,” answered Felix, “who would divide the world in quadrants, each in its own sphere. An old-fashioned and tried-and-true imperialism in its own right.”

“I can see it is a waste of time to argue further with words,” Richard said. “You will not understand the righteousness of our rule, as you are married to unjust, traditional practices. We will blast you from the field.”

Richard signaled to his soldiers, who began to cry at the top of their voices, and amid their shrieks we could hear repeated the word “judgment,” though the din was great. As they bobbed in their saddles, the dance of the sparkling Js on their helmets created a comic effect.

Sir Felix turned to us and explained that he had seen similar judgmentalists before, in Berlin, Kolkata, Naples, and New York. They all made noise, he said, to intimidate others, and drew strength from the narrowness of their dogma.

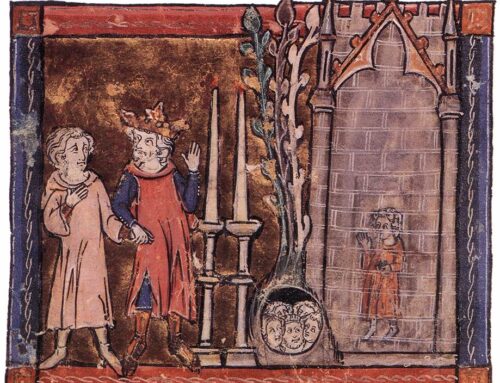

He waited until the shrieking exhausted itself. Then he asked Richard whether he would have the mettle to settle their conflict in single combat. They would joust, and whoever was unhorsed would admit defeat. “He may think of himself as mighty Maleagant in his arrogance. But if he is Maleagant, I will be Lancelot.”

Richard was only too happy to accept the challenge. He had fought across the oceans for the Order, he said, and always emerged victorious.

The two knights equipped themselves with their lances and faced each other across the plain. Richard’s lance the festooned with a black and silver J; Sir Felix’s bore the emblem of the red rose, an emblem, he always said, that contained secret power.

Richard spurred his horse toward Felix at a furious pace. Sir Felix noted that Richard’s path was well-trod, as this had been the course of many charges. He therefore guided his horse in a swerving motion. The maneuver led Richard to lean out over his high horse to reach Felix with his lance, and Felix, with subtle dexterity, caught his helmet with his lance, tipping the cleric to fall clumsily to the ground.

The knights of the Order stood there dumbfounded, even abashed, at their leader’s fall. “I hooked him on his own J,” Felix said simply, and we continued our passage across the plain.

Felix Kaufmann, virtute praeclari scientia incomparabilis sapientia primi inter pares, in piam memoriam.

Leave A Comment