Gardens and the Healing Arts (Timothy Kircher, Sartle.com)

Fresco from the Garden of Livia Drusilla, Museo Nazionale Romano, Palazzo Massimo. Source.

As the neurologist Oliver Sacks noted, gardens are places of healing. The Greek root of therapy could mean cultivating the land, and so Sacks wrote that “in many cases, gardens and nature are more powerful than any medication.” Perhaps for that reason artists have felt themselves drawn to gardens: they offer a balm, a place to rest and reflect on time, eternity, and beauty. If we survey gardens in art, we see that different peoples and cultures have venerated them for a greater sense of personal wholeness and belong, for feeling connected to the natural world and the world beyond.

Classical Gardens: The Garden of Livia

Livia Drusilla, the wife of Octavian, later Emperor Augustus, commissioned artists to create an imaginary frescoed garden underneath her villa outside Rome. Legend has it that Livia was inspired to build the villa around the time of her marriage, when an eagle dropped a white hen in her lap (a wedding present difficult to return). The hen had a laurel branch in its beak, and Livia took the cure to cultivate both the hens and the laurel. The artists in turn decorated the four walls of the underground chamber with laurels and twenty-two other species of plants, and also dispersed images of poultry and five dozen other birds among their foliage. Livia found repose in this 20×40-foot painted garden, a shelter not only from the summer heat but also from the burdens of being wife to one emperor and mother to another (Tiberius, who hated her, but that’s another story). One of the wonders of this work is that it was painted underground, with no natural illumination, yet it captures the sights, sounds, and fragrances of an idealized natural world.

Large view of Fresco from the Garden of Livia Drusilla. Source.

Detail from Fresco from the Garden of Livia Drusilla, South Wall. Source.

Medieval and Renaissance Gardens

During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, gardens alternated as places of spiritual serenity, sensual pleasure, and suffering: they represented different aspects and possibilities of Christian life. Mary, when she hears the angel Gabriel hailing her as the mother of Jesus, often sits in a walled garden with a book before her. The closed or walled garden – in Latin, hortus conclusus – signifies Mary’s virginity as well as her quiet introspection, her seclusion from outside noise and distraction. On example is the scene from the monastery of San Marco in Florence by Fra Angelico:

Fra Angelico, Annunciation, San Marco Museum. Photo credit: Timothy Kircher.

The young Leonardo developed his feeling for the intimacy of the encounter in this painting, which viewers still experience today:

Leonardo da Vinci, Annunciation, Uffizi Gallery. Source.

In the sermons and writings of the time Mary comes forth as a second Eve: Eva in Latin is reversed by Ave, “hail,” Gabriel’s first word to her (in Church Latin, not her native Aramaic!). So Mary reverses the fall of Adam and Eve, who were of course in their own garden of Eden. Artists like Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder portray this garden as a lost utopia of pleasure, with peaceful frolicking animals and the original nudist camp.

Rubens and Jan Brueghel the Elder, The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man, Mauritshuis.

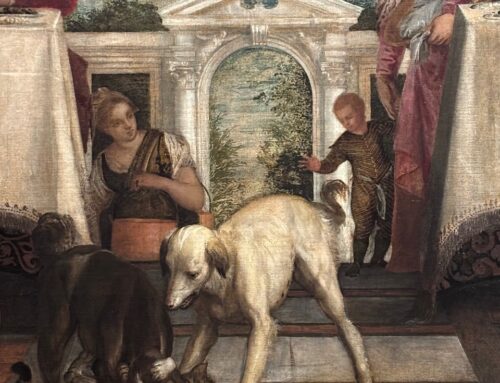

After their fall from grace, however, Adam and Eve were cast out from the Garden and had to make their way in the world, a place of tears, toil, and trial. But medieval and Renaissance artists still knew the pleasures of earthly gardens. The garden party was a scene in vogue, as in Buffalmacco’s fresco from the Campo Santo, the Holy Field, in Pisa. These fashionable tricentennials talk and play music, as if ignorant or heedless of the sickle of death hovering overhead. The fresco may have inspired the young Boccaccio to recount his Decameron tales in gardens, where his ten young narrators find a haven from the horrors of the Black Death.

Bounamico Buffalmacco, Detail from Triumph of Death fresco, Camposanto, Pisa. Source.

These garden pleasures, these new earthly delights, therefore often received a spiritual frame. Hieronymus Bosch portrayed these pleasures to the nth degree, much as he painted everything he saw, with corybantic and mysterious abandon. The central panel of his Garden of Earthly Delights shows a wild orgy of eroticized fetishes, a procession of unbridled sexual action. But Bosch was a member of the Illustrious Brotherhood of Our Blessed Lady, and he placed this garden vision in a triptych between the Garden of Eden and the dark, incendiary image of violent torment and damnation.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, Prado.

In this period of Christendom, spiritual serenity stood at the side of earthly sensuality, heightening a feeling for both. Humanity, forgetful of or asleep to the divine voice, required an intercessor who experienced and overcame their suffering in exile from the original paradise. Artists like El Greco captured this emotional trial of Jesus in a third garden, the Garden of Gesthemane or Garden of Olives. El Greco painted this scene around the same time as Bosch created his garden triptych. Christ’s beloved disciples slumber in the foreground as monuments to human weakness; he pleads with his Father to spare him his sacrifice, even as his right hand reaches for the cup, offered by an angel, that seals the deal. Behind him the mob gathers to take him to his death. Divine light brightens the darkness, fully engulfing the angel and cascading down to the disciples’ faces and folds of clothing. The mob, by contrast, has only human torches for illumination.

El Greco, Jesus in the Garden of Olives, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes.

Islamic gardens

During the same period, Islamic artists were both designing gardens and illustrating them as an abode of paradise – the word paradise has Old Persian roots meaning “walled enclosure.” In Babur supervising the laying out of the Garden of Fidelity, the painter Nanha shows the Mughal Emperor (1483-1530) at the gate, taking a hand-on approach to the four-fold plots decorated with trees and flowers outside Kabul.

Nanha, Babur supervising the laying out of the Garden of Fidelity, Victoria and Albert Museum.

In another image, he directs the construction of the garden at Istalif, standing over a reflecting pond that flows out to irrigate the grounds. The design and features offer both religious meaning and physical comfort; these gardens provide spaces for calm contemplation and also delight the senses.

Asian gardens

On every scale, from the humblest to the grandest, Chinese artists presented their imaginary gardens as places of refuge. At times they appear as busy salons for poets to meet and even compose verses celebrating the occasion. But, as in Wen Zhengming’s (1470-1559) ink drawing of The Garden of Pleasure in Solitude, a figure sits gazing out from a pavilion over a tree-lit and mountainous landscape, while a servant stands ready to serve him. This may have been a retreat, like visiting a Daoist or Buddhist temple, where air and scenery granted the viewer a moment of renewal.

Wen Zhengming, The Garden of Pleasure in Solitude, National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Modern gardens

All these qualities – renewal, beauty, peace – inspired Claude Monet to build his garden at Giverny, which he painted over 250 times to capture the changing daylight and seasons. Monet’s particular genius lay in his understanding of time; like Titian, Monet continued to paint with failing eyesight, so that his paintings of his garden record not only the seasons of nature but also the ages of life, time passing in the life of the artist (and viewer). Time has entered the garden, even as each painting suggests a moment of rest and repose.

Claude Monet, Japanese Footbridge, National Gallery of Art.

In the “modern times” of Monet we can see snapshots that preserve time in its passing. Eugène Atget created garden art with his large-format camera, showing us growth and decay, blooming flowers and scarred stonework, or trees without leaves, as in his photo of his beloved Saint-Cloud from 1922. The trees are both wild and artfully framed; they display their trunks in the stillness of water, forming a wall that is yet transparent. The line between nature and artifice enters the artwork itself, for Atget lets us sense, self-consciously, how we create our own gardens, shaping and cultivating our own nature in response to life around us.

Eugène Atget, Saint-Cloud, Getty Museum.

Oliver Sacks took his patients to the New York Botanical Garden. Designers like Frederick Law Olmsted created vast public gardens as green lungs in urban centers, as sites for recreation, health, and healing. Visual artists offer their own salutary perspectives; their paintings are windows into both nature and our inner lives.

Works of Art Referenced for Further Reading:

Classical Gardens

Medieval / Renaissance Gardens

- Annunciation by Fra Angelico

- Annunciation by Leonardo da Vinci

- The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man by Jan Brueghel the Elder and Peter Paul Rubens

- Garden Party detail from The Triumph of Death by Buonamico Buffalmacco

- The Garden of Earthly Delights by Hieronymus Bosch

- Jesus in the Garden of Olives by El Greco

Islamic Gardens

- Babur supervising the laying out of the Garden of Fidelity by Nanha.

- Babur supervising the laying out of the Garden at Istalif

Asian Gardens

- The Garden of Pleasure in Solitude by Wen Zhengming

Modern Gardens

Further works of art featuring gardens:

- Salisbury Cathedral from the Bishop’s Garden by John Constable

- Memory of the Garden at Etten by Vincent van Gogh

- A Tale from the Decameron by John William Waterhouse

- Celia Thaxter’s Garden, Isles of Shoals, Maine by Childe Hassam

- The Kitchen Garden in the Eyot by Leonora Carrington

h/t Jeannette Sturman and Rick Love

For other posts on gardens, see here.

For a related post on trees, see here.

For other posts on the arts and health, see here.

Leave A Comment