The Healing Place of Trees in Art (Timothy Kircher, Sartle.com)

Vincent van Gogh, A Wheatfield with Cypresses, 1889.

In Robert Frost’s poem, “The Sound of Trees,” the poet asks, “I wonder about the trees. / Why do we wish to bear / Forever the noise of these / More than any other noise / So close to our dwelling place?” The poet’s self-mocking question speaks to the way artists have portrayed trees “so close to our dwelling place.” If one looks, one finds them everywhere as totemic icons, archetypes, figures for nature, and more. Throughout cultures and societies, trees have offered artists a symbol for nature conceived as a unity, in its wholeness, as the writer discovers in Frost’s poem. From their roots to their branches, they connect the realm of the ‘physical’ and ‘non-physical,’ sensible and supersensible worlds. In other words, artists consistently depict trees to show us a deeper awareness of our whole nature, embracing but also transcending our transient, material selves.

Ancient art

Among the African San people, tree and botanical images strongly correlated to their spiritual life. It is not surprising that among the most ancient examples in African rock art that trees appear frequently, in combination with animal or human figures. In this prehistoric drawing from Zimbabwe, we can see the significant size of the tree compared to the surrounding human figures, one of whom approaches it:

This image from the Egyptian tomb of Khnumhotep II (tomb 3), dated to 1900 BCE, shows birds taking refuge in an acacia tree. While there are several trees sacred to the Egyptians, the acacia was the wood used in the barge of Osiris, the god of nature, who “died” each year in the autumn, but came to life again in the spring. The acacia therefore represented resurrection and redemption, the tree that sheltered Osirus, the god of the underworld and new life. The son of Osirus and Isis, Horus (sometimes merged with Ra, the sun god), traverses the sky on a barge flanked by the acacia and the date palm, as he navigates between day and night.

Among the Assyrians, as in this carving from the 8th C. BCE (at the site of Nimrod / Kalkhu, now in the Iraq), the Egyptian myth fostered the image of the Tree of Life. Here the tree is a cedar, visited by a winged spirit, who picks the cone from the tree.

The Tree of Life became a central figure in many societies, such as the Cypriot funerary stele from the 5th C. BCE:

Mesoamerican art

Among Mesoamerican peoples, the Tree of Life or “world tree” showcased the four cardinal directions as well as linking the underworld, earth, and heavens. This Western Mexican tree, from a pre-Columbian shaft tomb, features birds, which may represent souls on their way to the afterlife:

The sarcophagus of Kʼinich Janaab Pakal I, a 7th-C. Mayan ruler, shows a cross-shaped world tree or Tree of LIfe on the central axis, as the ruler enters the underworld through the mouth of a serpent:

Norse / Germanic art

Corresponding to the archetypal Tree of Life images is the Norse Yggdrasil, the sacred ash that has roots far beneath the earth and branches extending into the sky where the gods dwell. The gods gather in assembly every day and one of the wells that feed the roots, Mimisbrunner, is considered to contain water of wisdom; another well, Urðarbrunnr, contains the fates that govern human lives. The German-American painter Friedrich Wilhelm Heine illustrated the tree, showing an eagle surveying the world:

In contrast to the eagle, the dragon Níðhöggr gnaws at the roots deep in the underworld, and in the lake feeding the tree Heine has placed a snake biting its tail, an ouroboros or a symbol of the eternal cycle of life.

Corresponding to the Yggdrasil was the Saxon Irminsul, the legendary tree that Charlemagne destroyed in his forced conversion of this tribe. It lived on like the Yggdrasil as a Tree of Life, for example in the 12th-C. capitals of the monastery at Hamersleben and other places, splicing together, as art has always done, the elements of various religious and artistic traditions.

Abrahamic art

As the medieval Hamersleben cloister indicates, the Tree of Life found its place in each of the major Abrahamic faiths.

In Islam, it was a common feature of the mihrab or prayer niche, for example in this 16th-C. mihrab from Isfahan in Iran:

The Qur-anic inscription surrounding the niche cites the Chapter of Light (24:35), which proclaims that God’s light, like a star, is lighted from “a blessed tree…the olive neither of the East nor of the West…” In similar fashion, the Tree is a common feature on Muslim prayer rugs.

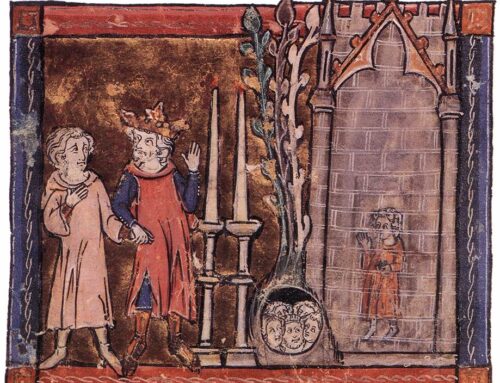

In the Book of Genesis, the Tree of Life (Etz Chayim or Hayim) is mentioned before the fateful Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil (Etz Ha’daat Tov v’Rah). The Tree of Life is therefore a prime image in Judaism, bearing fruit as we shall see in the paintings of Marc Chagall. Artists portrayed it not only in its literal form but also as a symbol for the all-encompassing knowledge found in Kabbalist mysticism, as it does in this illustration thought to be of the 13th-C. thinkers Isaac the Blind (Yitzhak Saggi Nehor) or Joseph ben Abraham Gikatilla: he ponders the sefirot, or ten linked emanations of the Divine Being, whose energy constantly creates both the material and the spiritual realms.

Image of the frontispiece of the Portae Lucis (Shaarei Orah) by Abraham Joseph Gikatilla, Augsburg 1516

This Kabbalist figuration of trees carries its own artistic legacy, which we can witness in Eli Content’s stained glass window in the Jewish Historical Museum in the Netherlands:

Christian teachings inspired artists to combine the images of the Tree of Life, the Tree of Good and Evil, and the Cross, in various forms. One obvious descendant is the ubiquitous Christmas tree, an evergreen that commemorates the birth of the Savior Jesus Christ. It draws on the legacy of the Yggdrasil, the Irminsul, as well as the Mediterranean precedents, as in the Glade jul of Viggo Johansen:

Or in more subdued fashion in the art of Jószef Rippl-Rónai, who contrasts the splashes of Christmas color with the figures in black:

The Christmas tree is characteristically a place of gathering and family, and the art emphasizes that identity.

In addition, the tree in Christian art has illustrated salvation history, the arc of providence from Adam to Christ. In artists’ figurations, the Tree of Good and Evil, the tree of the Fall, formed the original breach between humanity and God:

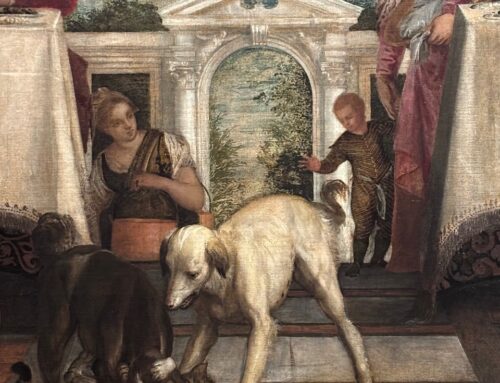

Yet a widespread medieval legend attributed the wood of the Cross to this tree of original sin, and artists reminded their viewers that Adam’s sin, punished by death, was atoned for by Christ’s loving sacrifice, which promised eternal life. In the fresco on The History of True Cross by Piero della Francesca in Arezzo, the artist displays various phases of this legend by showing the death of Adam painted above a scene depicting the Queen of Sheba worshiping the beams of that Tree, before her marriage to Solomon. According to this legend, Romans later used wood from the same tree in the Crucifixion.

Photo credit: Timothy Kircher

To these combinations, pagan and Biblical, artists added another tree, the Tree of Jesse, which purported to show the genealogy of Jesse, the father of King David to Jesus. It is among the earliest illustrations of a “family tree.” Medieval artists frequently used stained glass to emblazon this image for the congregations, which we can see in this brilliant 14th-C. example from St. Mary’s Church, Shrewsbury, of the sleeping figure of Jesse at the base of the tree:

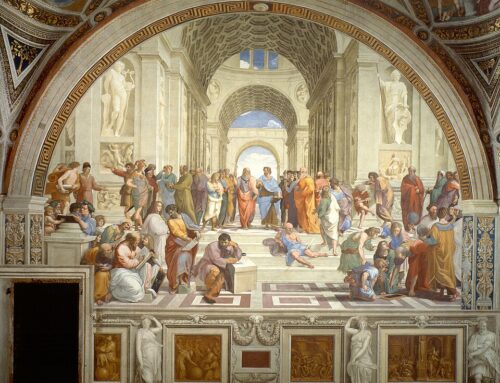

These genealogical trees could easily merge, too, in the artistic imagination with the roots and branches of learning established by the Kabbalist mystics, for example in the “Tree of Science” from the major work of the 13th-C. Catalan sage Ramon Llull.

Trees structured knowledge and understanding, the mental cosmos of their viewers, providing them both a sense of rootedness, of ancestry, as well as an orientation to their place in the order of things. Roots, trunks, and branches could become a roadmap for meditation. The 13th-C. Franciscan Saint Bonaventure composed his Tree of Life as such a roadmap, which quickly became a matrix for illustrating stages on life’s spiritual way. From this work, Taddeo Gaddi created a tree in Florence’s Franciscan church Santa Croce [Holy Cross], with the Crucifixion serving as a tree for phases of history and reflection.

Hindu Art

There are five trees in Hinduism found in the paradisal garden of Lord Indra: the Mandara; the Parijata or night-flowering jasmine; the Samtakana; the sandalwood; and the kalpa taru. Of these, Lord Krsna, at the behest of his wife Satyabhama, stole the Parijata tree and took it to their earthly garden, thus connecting, as with other sacred trees, the two realms of heaven and earth. In this 16th-C. manuscript, the blue-skinned Krsna and Satyabhama carry off the tree and he plants it in his city, Dvaraka, the “city of gates”:

Buddhist art

The sacred trees portrayed in Buddhist art include the teak tree, under which Prince Siddhartha’s mother, Queen Maya, gave birth to him, the future Buddha; and the sal or sala trees, among which he passed his final moments on earth. Artists especially emphasized his position before the sacred fig tree, for it was at this tree that he achieved nirvana after days and nights of deep meditation and became the Buddha. This tree became known as the Bodhi tree, or Tree of Enlightenment, commemorated in this Thai plaque from the 7th-9th century.

Chinese art

The Chinese have named the plum, pine, and bamboo as “the three friends of winter,” since they thrive in the colder months and offer examples of vitality in adversity. The pine is called “the Chief of the Trees”; its name, song, is also the word for the state of relaxation in meditation, where the body is aligned to circulate qi and receive heavenly qi. The pine is compared to an old, wise person, someone who has overcome challenges and thrives. The painting by Ma Yuan around 1200 shows a scholar under a pine, observing the rushing waterfall, whose waters symbolize the passing of time beneath the eternal branches of the tree.

Trees in Modern Art

Modern artists tapped into the legacy of the tree image. Odilon Redon painted the Buddha merging with the colors of the garden as he sits under the sacred tree.

As mentioned earlier, Marc Chagall painted scenes of the Tree of Life and Tree of Jesse, imbuing each with brilliant splashes of surrealism.

Sartle’s own Richard Love deepened the indigo in Chagall’s works when creating his elemental wall sculpture “Mississippi Indigo.” If indigo is said to symbolize integrity, wholeness, and intuition, even more fundamental are the trees chosen for the sculpture: ash, revered by the Celts for growth and expansiveness, a tree that held together earth and sky; and cedar, the Biblical tree (Ezechiel 31) prized for its deep roots and its height, a symbol of strength and majesty.

Photo credit: Richard P. Love

Artists sometimes endowed the tree with paradoxical, sometimes contradictory meanings, which is a way of paying homage to its totemic tradition. In an apparently less reverential way, René Magritte took on the Tree of Knowledge after World War I and showed it as gun smoke enclouding the words “sword” and “horse,” two antiquated munitions of past centuries. The earthquake of artillery and the senselessness of the Somme resound silently in the two puffs of smoke, expressing, as did writers and philosophers from Hemingway to Heidegger, the need to re-discover the meaning of life.

In between the reverential and the sardonically satirical lies Frida Kahlo’s nod to the Family Tree, the genealogical construct of Kabbalist and Christian artists. She turns the tree upside down, placing herself as a young girl at its root in her ancestral Casa Azul, and leaving her parents and grandparents swaying overhead.

This deeply anchored notion of connectedness and wholeness – among past, present, and future; and among earth, heaven, and humanity – is set subtly in the images of trees, for example in Paul Cézanne’s apparently ‘naturalistic’ watercolor of the Pine Tree in the Arc Valley, shimmering with Asian undertones.

Vincent Van Gogh, who was inspired by both Asian art and Cézanne, returned to painting trees again and again, as in this one of a mulberry tree in flame like the burning bush of Exodus.

In his final days of despair, he illustrates his torment by painting not trees of orange fire but the coils of tree roots, tangled in the earth. Gone is the upward sense of sky and light.

In another example of modern artists reversing perspective on the traditions of tree symbolism, Georgia O’Keefe adopted a new angle of vision in The Lawrence Tree, her striking painting of a ponderosa pine at the house of D.H. Lawrence. She has us look up into the branches that look startlingly like roots, so that the tree seems upside down, except we find orientation in the starry sky beyond it.

Her friend Ansel Adams traveled with her throughout the Western US, and he set a parade of trees in his delicately composed photographs. In a photograph from Yosemite, an ancient pine tree bends toward a stone monolith, as if in shared awareness of their heritage and their abiding meaning.

The artist and activist Ai Weiwei uses the tree image to express our contemporary weakness and strength. His Tree gains greater resonance in consort with the image’s history. If artists throughout the centuries presented us with trees that demonstrate the unity of the cosmos, Ai Weiwei shows us our brokenness: the tree is in fragments. Yet the ensemble is still intact, demonstrating the promise of wholeness.

Nature, spirit, wholeness, humanity: the tree throughout the history of art has portrayed these qualities. In the light, or the shadow, of Ai Weiwei’s sculpture, we can ponder the words of the healer and tai chi master Marshall Ho’o: “Consciousness sets us free, but it also cuts us off from that state of unquestioning participation in nature which is full of meaning. And so, we find ourselves situated at the threshold of a great void, which is our new home. The way of transforming this void into a place where human life can remain whole and integrated is called, in the Chinese tradition, the Tao.”

Wholeness is the sum of healing; both “whole” and “health” have their roots in the Greek hólos, a word that also conveys the ordered universe. Trees in art symbolize this universe; they offer us a bridge to wholeness and healing, to finding the richer meaning in nature. The poet in Frost’s “Sound of Trees” intimates this wholeness when he states that the trees “are that that talks of going / But never gets away; / And that talks no less for knowing, / As it grows wiser and older, / That now it means to stay.”

Recommending “Finding the Mother Tree” by Suzanne Simard for an exploration of how trees function in the interconnectedness of a forest ecosystem for further musing on wholeness as lived into by trees.