The real problem is not the politicization of history. After all, the hijacking of history for partisan and ideological ends isn’t new. What’s much more worrisome is the diminishment [sic] of the humanities and of the intellectual, cultural and artistic life more generally.

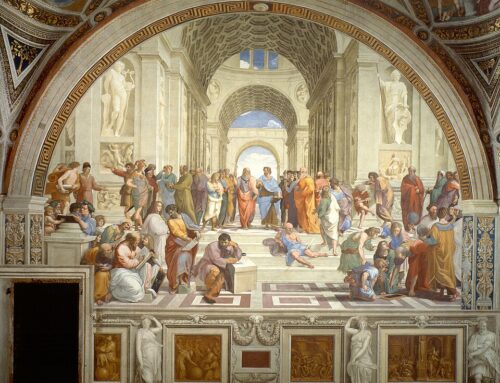

What we are witnessing is the decline in the rigorous, engaged, informed study of the arts, culture, history and philosophy.

Individual humanities departments quite naturally worry about a decline in the number of majors. But for those who care about the humanities as a whole, the most important issue is the relatively small number of students who graduate without a genuine grasp of humanities content and approaches….

Let’s not kid ourselves. Assigned reading, even in the most selective institutions’ humanities departments, has declined. Lower-division classes have, in too many instances, become overspecialized, reflecting their instructors’ narrow interests rather than considered, collective judgments of what students ought to know and be able to do. Sweeping humanities themes and concerns that cut across department lines are too often neglected. Worse yet, the skills that the humanities nurture—close reading, critical thinking, argumentative writing—can’t be taught in the kinds of performative, instructor-focused lecture classes that predominate.

This is how the humanities end….

The humanities does not simply consist of a body of texts, art works, facts and interpretations taught in classrooms. The practical, applied, translational, open and public humanities all seek to connect the humanities with broader publics beyond the campus….

If we want the humanities not merely to persist but to thrive, we’d do well to show students how key humanities issues play out in institutions like museums, as well as in the professions, public policy and private industry. The humanities, after all, are too important to be confined to the academy.

For related posts, see here.

Leave A Comment