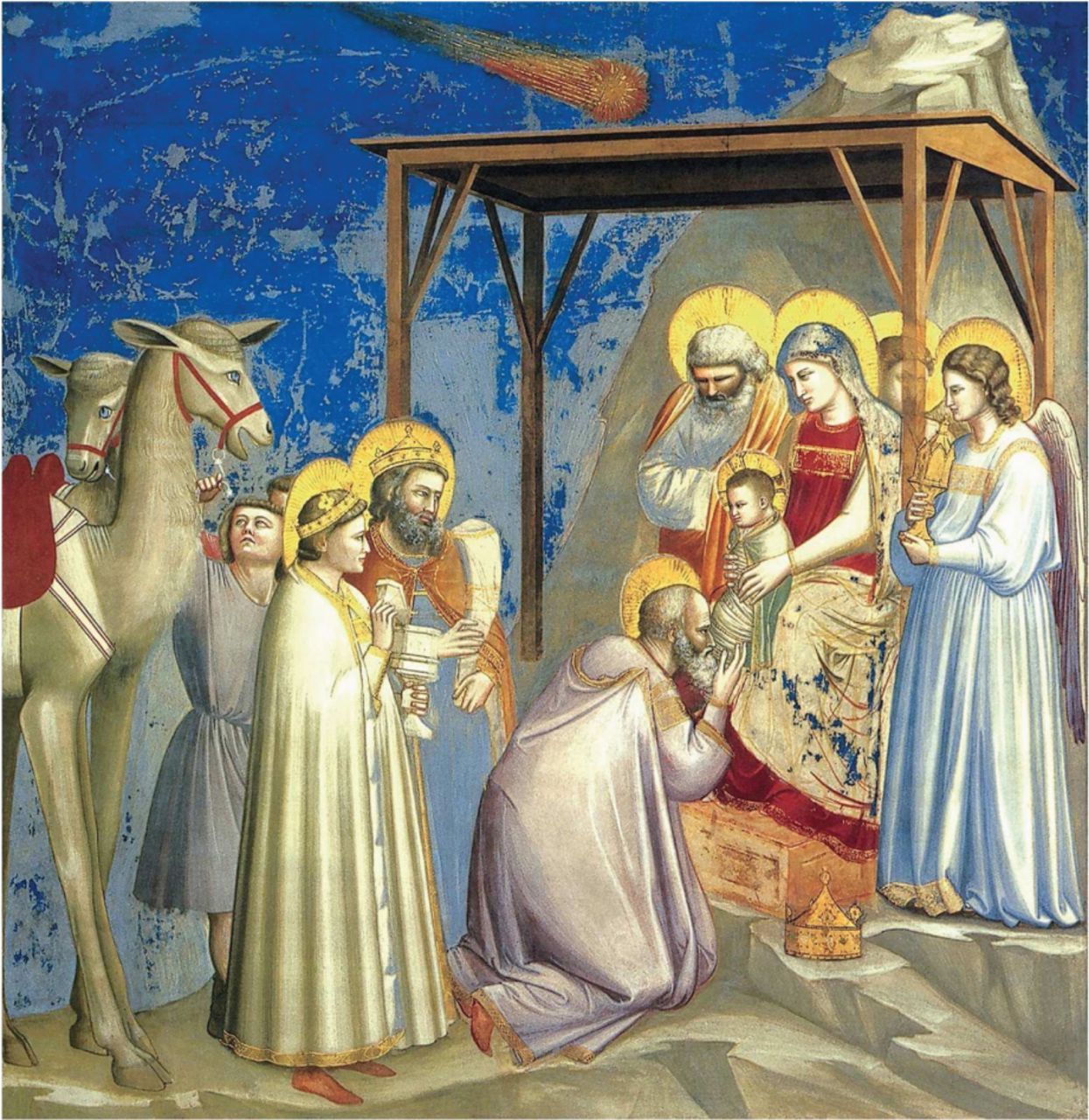

It could be said that in these early depictions the solar eclipse is part of the artist’s iconographic toolkit rather than treated as a precise physical event. However, it has been argued by Olson & Pasachoff, in their seminal essay on eclipses in art, that in due course the nascent science of astronomy came to influence artists. They cite the example of Giotto’s painting of the Star of Bethlehem in his Adoration of the Magi, being one of the key frescoes in Scrovegni Chapel in Padua….

Adoration of the Magi, Giotto; in the Arena Chapel, Padua, Italy

It has been argued that Giotto passed on his interest in natural phenomena to his pupil Taddeo Gaddi. He was partially blinded by observing an eclipse in Florence in July 1330. The suggestion is that Gaddi expressed his physical trauma in his nocturnal Annunciation to the Shepherds in Sante Croce. The shepherd shields his eyes from dazzling light and the angel almost looks as if it is eclipsing the Sun….

Annunciation to the Shepherds, painting by Taddeo Gaddi in Santa Croce Church in Florence, Italy

Artists could still have a real appreciation of the realistic features of a solar eclipse, but savour their use in a highly religious context. A fine example of this is a fresco created by Raphael and his workshop Isaac, Rebecca and Abimelech (1518–19) for the Vatican and some have suggested that it was no coincidence that the workshop may well have witnessed an annular eclipse that passed over Italy in June 1518. It is certainly plausible as that is precisely what is painted….

Isaac and Rebecca, Raphael

One serious contribution to the history of solar eclipses, and one that is both scientific and artistic, is that made by the Polish Lutheran astronomer Johannes Hevelius (1611–1689). One claim to fame derived from his observations of the Moon, which were published in his Selenographia of 1647 and were far more detailed and nuanced than those created by Galileo in his Sidereus Nuncius of 1610. However, perhaps the most striking fact is that Hevelius realized that improved observations needed to be matched by excellence in draughtsmanship and engraving worthy of publication and, therefore, he trained himself to engrave in copper, a work of great skill. Furthermore, unlike earlier scientific manuscripts in which text was dominant and images secondary, he was pioneering in producing works in which this was stood on its head, with the verbal text dependent on the dominant and splendid images….

Darkened Room illustration from Selenographia, 1647. Science Museum.

By contrast, much painting of this period was influenced by the teachings of a resurgent Catholic Church and a clear doctrine that divine power was revealed through natural forms. To some degree, this harks back to theology underpinning the ivories and manuscripts that we encountered earlier. One can see such thinking in increasingly vivid depictions of solar eclipses in paintings of the crucifixion, in which the partial eclipse seems to provide a more vivid image of a divine will in action than, for example, the annular eclipse we saw in the work of Raphael. Thus, Rubens painted a dramatic partial eclipse in the upper corner of the right hand panel of his Elevation of the Cross triptych created for Antwerp Cathedral in 1610….

Elevation of the Cross, Rubens, 1610

Leave A Comment