Mountain shadows, mountain light: how wholeness of knowledge comes from the cycle of greater vision

The student, perplexed, came to see Master Song.1

“Master Song, I don’t know what to tell you. I went to the US recently with a number of my classmates to see what I might study in college there, and I discovered among both my classmates and those in the United States a tremendous emphasis on sciences and technology. But I am interested in studying language and history, and knowing more through these branches of learning. So I am feeling more and more discouraged.”

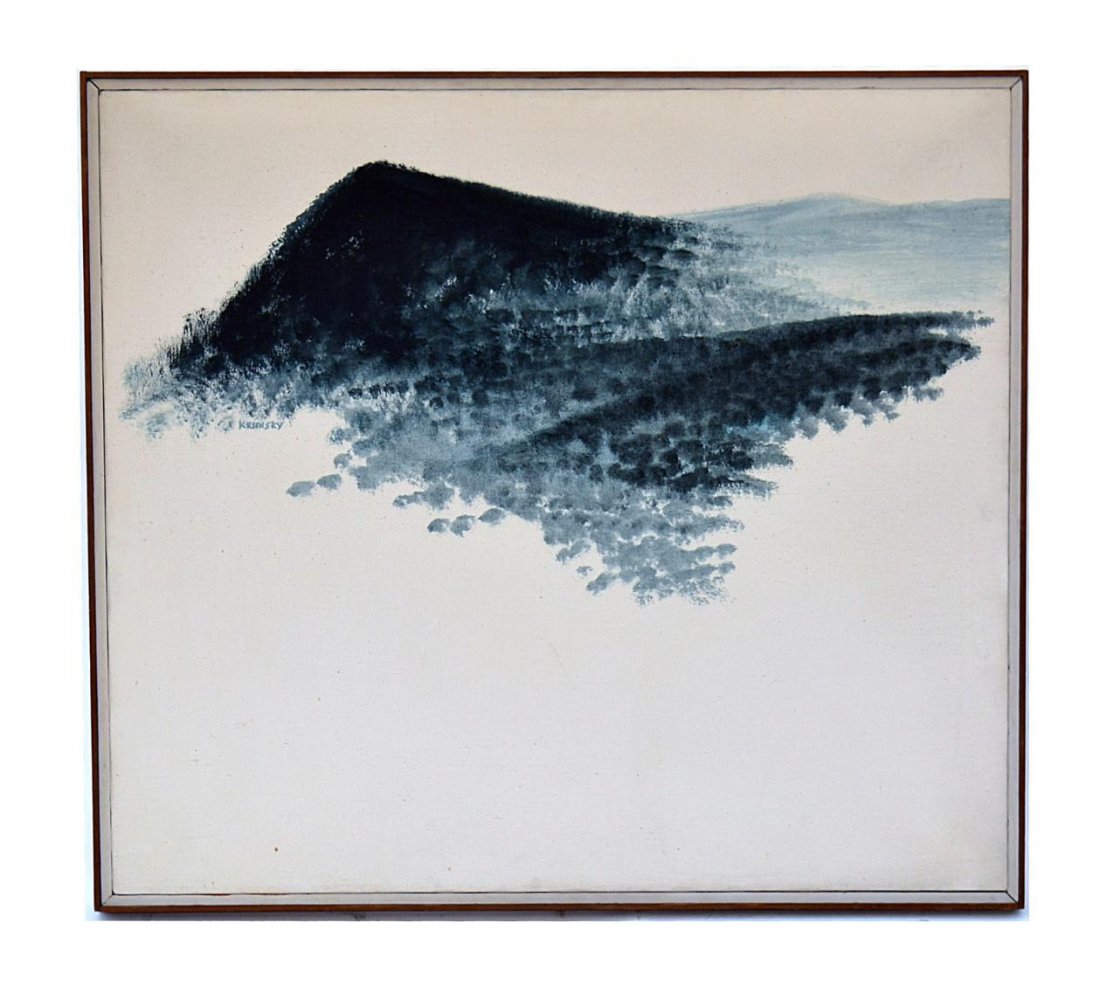

Master Song said nothing, but went to his window and opened the curtains. She could see, framed by the window, a mountain. One side of the mountain was glistening in the sun; the other side was cast in shadow.

“What are you showing me, Master Song?”

“There is one side in shadow and one side in sun. Those of you who wish to study languages and history feel yourselves in the shade, while those studying the sciences feel warmed by the sun of attention and the praise of their families.”

“Yes, that is true.”

“You have heard of yin and yang?”

“Of course.”

“Then you know that yin and yang are complements. Neither exists without the other. When yang is at its peak, there too is the beginning of yin. And when yin feels strongest, there too is the root of yang.”

“Yes. I understand this is the principle of the Tao.”

“But do you not recall the original meaning of yin and yang? Yin means, in its origins, the shady side of the hill (阴). It is the side that is sometimes described as passive, but it is also understood as patient and regenerative. Yang shows the sunlit side; it is often considered the active side. It is the side of action, and outward energy. But yang cannot exist without yin, no more than yin can exist without yang. The character for yang (阳) is the sunny side of the hill. You cannot have a sunny side without a shady side. And in fact, the sunlit side may seem more prominent when the shade is weak: but this is a false appearance, for the balance has been lost. For the hill appears most powerful when the two are in balance. There can be no strong yang without a strong yin.”

“I understand this, Master Song. But I don’t quite grasp the meaning of what you are trying to tell me.”

“You came to me right now and said you are being in shadow, obscured. But this is the way of the humanities. This is the way of language, history, and philosophy. For these find their strength in shadow. But being in shadow does not mean that they are any less necessary than the sciences that pride themselves for being in the sun. Many scientists understand this!

“Let me give you another example. There is an herb, there is a flower, there is a plant called heliochrysm. It grows on the sunny side of the hills in Corsica with beautiful flowers and alluring fragrance. It is often used in perfumes. Yet it also grows on the shady side of the hill. It is the same plant, though it often looks different in the shade. There the roots are stronger, and have been found useful in medicine and the healing arts. It is the same plant, though on one side it appears splendid, while on the other side it appears less distinguished, with greater humility. It is the same plant, but the splendid plant does not have the same healing properties as its humbler relation. That is what you must keep in mind. Both are valuable, but this value is seen when both are vibrant. A beautiful flower must take care that its roots are made firm through its inner properties of yin. Otherwise it will be easily torn up and discarded, like the lily near the river, as Leonardo da Vinci noted well. But be grateful for the sunlit sciences, for they show the strength of the humanities, at home in the shade, as complements to one another.”

h/t Tracy Peck and Zhihong Chen

1. song (松): “relax, loosen”↩

Leave A Comment