On American reading, technology, and intellectual life: thoughts from a European historian.

The newspaper in American society has become the real literature in the essential sense of the word. The newspaper fulfills in America the cultural function of the drama of Aeschylus. I mean that it is the expression through which a people – a people numbering many millions – becomes aware of its spiritual unity. The millions, as they do their careless reading every day at breakfast, in the subway, on the train and the elevated, are performing a horrendous and formless ritual. The mirror of their culture is held up to them in their newspapers, with more emphasis and persistence than in any novel….

For an “artist in words” cannot enthrall anyone whose attention and interest are of the slightest. A certain conformity to the literary taste of the day is naturally desirable. Now and then an unexpected or over-colorful adjective or fashionable turn of phrase catches the eye. But mysterious and fancy writing wearies and annoys the educated and the uneducated reader alike, and it probably does not even interest the half-educated man. For an American editor, boring the public means sinning against the Holy Ghost of democracy. What finally matters is to get and hold attention.

This aim has shaped a very important development in the writing style of American newspapers. There is a very deliberate striving to reduce the effort of thought required, and to capture attention. In practice, therefore, the overwhelming bulk of reading matter becomes very limited in character….

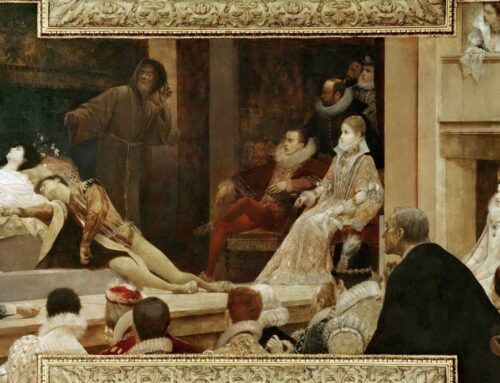

Pictures break us of the habit of thinking and they heighten the superficiality and inability to concentrate that ceaselessly threaten modern intellectual life. The European traveler finds it almost impossible to concentrate when he is in a big American city. The telephone becomes a curse. The variety of personal assistance and technical devices causes as much diversion of attention and loss of time as it saves work.

Johan Huizinga, essay on American society, 1926; trans. H.H. Rowen

Leave A Comment