La prima novella dell’Endecameron: l’esilio sotterraneo del contadino Latini

Una delle novelle più singolari del Decameron la raccontava mio nonno Amerigo che, preso dalla fantasia dell’opera, aggiunse di sua sponte questa storia, a dir suo, raccontata l’undicesimo giorno del ritiro dell’onesta brigata. Stanchi di ascoltare dieci novelle per dieci giorni consecutivi, l’undicesimo ne fu narrata una sola, ma tanto significativa – diceva lui – che bastò per una giornata intera.

Il narratore d’eccezione è Antonio Latini, intelligente contadino legato con convinta coerenza alla sua condizione di cui seppe cogliere, con la fatica, tutta la parte positiva e ricca di complesse e profonde conoscenze degli uomini e dei misteri della natura e del mondo. La novella racconta di suo padre, anch’egli contadino, la cui memoria rimane ancora oggi in alcune leggende che si raccontano nel paesino di Fara in Sabina: era un uomo, come si diceva allora, che “sapeva arare dritto come nessuno”. I suoi solchi, tracciati con matematica precisione, erano considerati esemplari. Grande domatore di cavalli e di buoi, era giocatore e bevitore imbattibile.

La storia, narrata dal figlio, risale agli ultimi anni Quaranta del Trecento: era una di quelle implacabili e torride estati che bruciano inesorabili ogni forma di vita vegetale e spossano, sfibrandoli, uomini e animali, lasciando sopravvivere soltanto il verde intenso e trionfante dei vigneti, il verde livido degli ulivi e l’arido, incessante canto delle cicale.

In questa calura senza scampo, l’uomo dai solchi dritti, il domatore insuperabile di bestie selvagge, il dottore sapiente che conosceva e guariva anche i mali dei buoi e dei maiali, volle concedersi una vacanza, la sola che ebbe nella sua vita di lavoro duro e assiduo. La vacanza che si scelse gli venne suggerita dall’unico sollievo che gli dava la vita: il vino. La vendemmia del 1347 sembra che, almeno in quelle terre, fosse stata abbondante e il vino, nonostante l’imperversare della peste nera, generoso.

L’ultima botte di cinquecento litri, scampata dalle bevute dell’inverno e a quelle del duro travaglio della mietitura, restava fresca e solitaria nella grande grotta adibita a cantina che scendeva sotto la terra spaccata dal sole.

Il padre di Antonio Latini decise che proprio in quella grotta avrebbe trascorsi, lontano da tutti, uomini e bestie, e soprattutto da quella immobile e accecante stagione pestifera, i giorni della sua sosta, del distacco dal morbo che stava affliggendo il mondo. Insieme a un suo compare, anch’egli tra i primi bevitori del paese, decisero di chiudersi nella grotta-cantina di cui qualche fievole raggio di sole illuminava la prima parte, lasciandone in penombra e al buio i più lontani recessi.

Proibito a tutti, familiari e amici, di avvicinarsi all’ingresso del rifugio o di chiamarli per qualsiasi motivo (erano uomini temuti e quindi nessuno fiatò o ebbe a ridire su questa stravaganza), si calarono scalzi nella sotterranea dimora, carichi di un enorme prosciutto, di un’infornata di pagnotte e di un mazzo di carte. Questa vacanza totale, lontana dalla realtà del mondo, sembra durò intorno ai venti giorni. «Va e mangia il tuo pane con gioia e bevi il tuo vino con cuore allegro», fecero appunto come consigliato dall’Ecclesiaste (9:7).

Verso la fine del mese, consumati prosciutto e pagnotte e scolati fino all’ultima goccia i cinquecento litri di vino, i due compari, che si erano nel frattempo scordati, in centinaia di partite a scopa, a briscola, dell’esistenza del mondo e di ogni suo penoso impegno, riemersero dalla penombra tra lo stupore dei pochi familiari e amici scampati alla terribile mortalità della peste.

Quel loro incomprensibile esilio e quell’immane bevuta – dodici litri a testa pro die – gli salvarono la vita protetti dal grembo della terra.

Il giorno dopo il padre di Antonio Latini riprese, e fino alla fine della sua non lunga stagione umana, il duro lavoro: tracciò solchi sempre più dritti, consultò gli astri per regolare le sue colture, piegò al giogo e alla stanga giovenchi e puledri sempre più restii, curò sapientemente mucche, cavalli e pecore e non si staccò più, fino alla morte, dalla pesante realtà della sua esistenza.

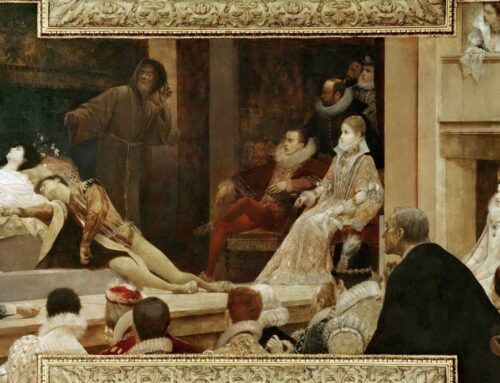

Quel breve esilio dalla vita in solitaria orgia sembra un grande mistero dionisiaco: forse il padre di Antonio Latini e il suo compare resero, inconsapevolmente, un grande omaggio agli dei nel momento in cui la Natura, senza scrupolo alcuno, imperversava sulle vite umane.

E così si salvarono, come ancora oggi viene raccontato nelle campagne della Sabina, perché qualcuno doveva continuare, anche dopo la pandemia, a mandare avanti la vita nella sua ciclica e quotidiana normalità.

Day 11: First story: the underground exile of the farmer Latini (trans. Timothy Kircher)

One of the most singular novellas of the Decameron was told to me by my grandfather Amerigo, who, taken by the work’s imaginative richness, added on his own this story that, to use his phrase, recounted the eleventh day of rest among the honorable group. The young Florentines were tired of listening to ten stories over ten consecutive days, so on the eleventh only one story was told, but one so significant that – as he said –it sufficed for an entire day’s worth of tales.

The exceptional storyteller is Antonio Latini, an intelligent farmer who, while bound with fixed ties to his condition, knew the means of cultivating, with determination, all the positive aspects that were filled with complex and profound knowledge of humanity and the mysteries of nature and the world. The story tells of his father, also a farmer, the memory of whom persists even today in certain legends that still echoed in the little commune of Fara in Sabina. He was a man, as they said then, who “knew how to plow straight like no one else.” His furrows, dug with mathematical precision, were seen as exemplary. A great trainer of horses and cattle, he was also an inveterate gambler and drinker.

The story the son told takes place in the last part of the 1340s. It was one of those merciless, horrid summers that burn relentlessly very form of plant and exhaust, wearing them down, both people and animals, allowing only a few things to survive: the intense and triumphant green of the vines, the bright green of the olives, and the harsh, incessant chirping of the cicadas.

In this inescapable heatwave, the man of straight furrows, the incomparable trainer of wild animals, the wise doctor who knew and also healed the illnesses of cattle and pigs, sought a respite, the only one he had in his life of hard and unremitting work. The “vacation” that he allowed himself was suggested by the only pleasure life granted him: wine. The harvest of 1347 seemed to have been, at least in this region, rather rich and the wine, despite the rampage of the Black Death, of generous quantity. The last barrels of 500 liters, unscathed by the winter drinking and the thirst brought by the hard labors of the harvest, remained cool and alone in the great grotto assigned to the cellar that lay beneath the earth ravaged by the sun.

The father of Antonio Latini decided that he would spend his days of rest precisely in this grotto, far from everyone else, humanity and beast, and above all from that fixed, blinding season of plague, apart from the illness that was scourging the world. Together with his accomplice, like himself among the first rank of drinkers in the province, they chose to seclude themselves in the grotto-cellar, whose opening was illuminated only by the feeble rays of the sun, while the lower recesses remained in shadow and darkness.

Having forbidden all, both family and friends, to approach the entrance of their refuge or to call on them for any reason (they were imperious men and therefore no one breathed a sound or had any rejoinder to this extraordinary enterprise), they climbed down barefoot into their subterranean refuge, supplied with an enormous side of prosciutto, a mass of bread, and many decks of cards. This absolute escape, far from the reality of the world, seemed to last about twenty days. “Go and eat your bread with joy and drink your wine with a happy heart,” they did exactly as advised by Ecclesiastes (9:7).

Toward the end of the month, have consumed their prosciutto and bread and emptied to the last drop of the 500 liters of wine, the two boon companions, who had forgotten quickly, in hundreds of hands of scopa, of briscola, the existence of the world and all its heavy tasks, re-emerged from the shadowy darkness and encountered the surprise of their few family and friends that had escaped the terrible mortality of the plague.

What seemed incredible to them was their exile and the immense effort at drink – 12 liters each, every day – that saved their lives protected in the lap of the earth.

The day afterwards the father of Antonio Latini continued his hard work until the remainder of his life: he plowed furrows always in a straight line; he consulted the stars to help determine the seasons of planting and harvest; he bent to the yoke the innately stubborn oxen and plow horses; he treated his cattle, horses and sheep with care; and he did not shy away, up to the moment of his death, from the heavy burden of his existence.

This brief exile from life in solitary orgy seems a great, Dionysian mystery. Perhaps the father of Antonio Latini and his companion presented, unwittingly, a grand offering to the gods at the moment in which Nature, without any scruples, raged against human lives.

And thus they saved themselves, as the story is still told today in the countryside of Sabina, because everyone had to continue, even after the pandemic, to move forward with their lives in their cyclical and daily routine.

For other posts from Coronavirus Tales, see here.

For sharing your own Coronavirus Tale, see here.

Leave A Comment