Hawks and Yawps: finding the humanities on an empty campus during a pandemic, spring 2020

I

Times of sickness are always times of introspection, and as I age in body and mind past 50, I am encouraged to go back to the humanities in the hope of feeling human again: to revisit favorite old books from my undergraduate days in particular that remind me of the vitality of my original self when I first immersed myself in my major, English. At the time, that consisted of mostly canonical American and English literature.

I loved nature poetry in particular in college and found a strange, wild energy in Ovid, in Marvell, in the Romantic poets and in their American cousins, the Transcendentalists. So I’ve picked up Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself” in Leaves of Grass (The Penguin Classics “First (1855) Edition”) in these doldrums with the hope of recapturing my youth and renewing my faith in my country.

Whitman is strange and wild and a rowdy advocate for human contact with nature and itself. He is thus the perfect antidote for being cooped up in isolation: open his poetry and you open a window to vibrant summer outside, including animals and people paradoxically photographed in perpetual motion alongside each other:

I think I could turn and live awhile with the animals . . . . they are

so placid and self-contained,

I stand and look at them sometimes half the day long.

They do not sweat and whine about their condition,

They do not lie awake in the dark and weep for their sins,

They do not make me sick discussing their duty to God,

Not one is dissatisfied . . . . not one is demented with the mania of

owning things,

[….]

So they show their relations to me and I accept them;

They bring me tokens of myself . . . . they evince them plainly in

Their possession.

I do not know where they got those tokens,

I must have passed that way untold times ago and negligently dropt

them,

Myself moving forward then and now and forever,

Gathering and showing more always and with velocity,

Infinite and omnigenous and the like of these among them (st. 32)

Whitman celebrates our common “velocity” in body and mind and “omnigenous” bonds with animals. Unknown to him but prophetically glimpsed, we recall the astonishing fact that humans have the same number of genes as a dog and not twice as much as a fruit fly (24,000 vs 14,000). Whitman is eternally expansive, wanting to inseminate everything, spooling out his verse in gobs of thought connected to one another loosely in flight [“On women fit for conception I start bigger and nimbler babes,/ This day I am jetting the stuff of far more arrogant republics.” (st. 40)]. So too with the animal world.

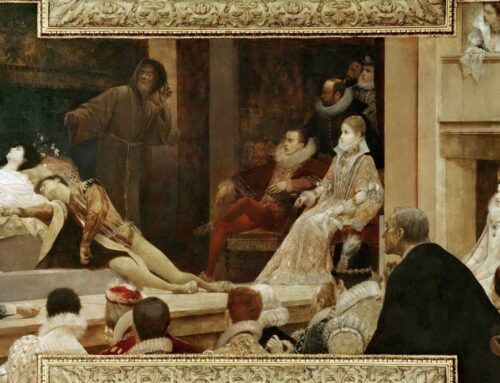

As King Lear puts it, cynically, also sitting mad in a meadow, “The wren goes to ‘t, and the small gilded fly does lecher in my sight.” Lear is angry that nobody obeys him anymore. But not Whitman; he wouldn’t care if he commanded an army or an ant. Few before or since have been more democratic or ruddy as Whitman. Whitman captures in his arms and mind the energy and breadth of our Continent in much of its diversity. He wants to be its diversity, seen from the perspective of bustling Brooklyn soon before our nation tore itself in half. Despite Leaves of Grass being first written before that great cataclysm, the Civil War, war and death and sickness are at its heart, quite literally. Whitman would go on to spend many days tending sick soldiers in field hospitals on the DC Mall, if not in Central Park. In “Song of Myself”, he knows the terrible sympathies and risks of the primary caregiver:

Not a cholera patient lies at the last gasp, but I also lie at the last gasp,

My face is ash-colored, my sinews gnarl . . . . away from me people

retreat.

Askers embody themselves in me, and I am embodied in them,

I project my hat and sit shamefaced and beg.

I rise extatic through all, and sweep with the true gravitation,

The whirling and whirling is elemental within me. (st. 37)

By the end of his whirling poem (which never really ends), Whitman is not afraid of death and sees himself transformed into leaves of grass growing everywhere for us to admire in their and his life cycle, spun out to infinity. Whitman wrote before grass became a preciously confined resource, placed beneath warning signs, having to be guarded against being built on or trampled on by too many tourists or chemically invaded to stay green.

II

The strange doldrums we’re in have encouraged me to go for long walks including, as destination, my campus, which is now a different world. I can revel in its natural beauty while I see and offend no one and get in nobody’s way, and no one offends me. I can avoid overcrowded classrooms in anodyne buildings, and I see no downturned, despondent faces of fellow faculty after twelve straight years of budget cuts, cancelled sabbaticals, and pay freezes.

Instead, Spring in the Deep South pulls me in: unblotted elm trees along our avenues (including Elm St) and longleaf pines, majestic oaks (with, dangling over the Tar River, Spanish moss), the gorgeous landscaping of dogwoods and azaleas, all under fine sunny weather in the 60s and 70s. No mosquitoes yet. The near complete lack of people on campus makes its old heart feel Edenic. Campus, true to its etymological roots, becomes a field again. I see no faculty nor staff and only a couple of students (probably athletes or foreign nationals who can’t get home). I have left behind my family cares and, ironically, my university: everyone has vanished, buildings are locked and the library is closed, and the bureaucracy is now online. I have come to university to escape my university. I have become Whitmanian, albeit a bit lonely: an idle scholar lounging at ease in a world of books amid the green.

Poetry allows life on campus to be seen simultaneously from above and within. Like Marvell’s speaker in the poem “The Garden” (pub. 1681), I look to the trees for reflections of light. I too am becoming “a green thought in a green shade”:

Here at the fountain’s sliding foot,

Or at some fruit tree’s mossy root,

Casting the body’s vest aside,

My soul into the boughs does glide;

There like a bird it sits and sings,

Then whets, and combs its silver wings;

And, till prepar’d for longer flight,

Waves in its plumes the various light.

That would be our Trustee Fountain, dedicated in the middle of our last financial crisis, in 2009. While Marvell escapes his body’s bounds by such a fountain, I imagine Whitman would take his shoes off and happily wade into it. Whitman is far more copper and brass than Marvell’s “silver.” There is far more blood in him, more German rust than Latin rus in his rusticity. But he is equally transcendent.

There is also danger in Whitman: an earthy, burly masculinity that campuses fear nowadays and try to contain, to restrict to stadiums, frat parties, intramural fields and weight rooms. But students need to grow, they want to learn and get ahead and are stressed and feel confined as they push forward by nature and are bent trying to do so. While faculty are retiring in the current crisis, our students are getting warped stuck at home behind a screen.

Whitman would have hated this. He was called the “good grey poet” (today sometimes the “good gay poet”) but he is not a careful or feeble old man in “Song of Myself”, not at all. Rather, he is a slowly aging fountain of youth, a fire hose not a trickling spigot, openly embracing men and women alike, sick and healthy in a desire to “merge” with everybody in body and soul in a feeling carelessness and profound democratic sympathy. He is rough and strong and kind and contradictory; he is spontaneous. I imagine he would have hated the cold distancing of computers, just as he would have hated the modern overbuilt campus, which is so litigious and bureaucratic and timid and sadly fearful of free speech. Like Coleridge in Xanadu, Whitman is dreamy, unpredictable, earthy and mystical, bursting: anything but slick, technocratic, and quarantined.

III

Just outside my office, which is in an old converted faculty dorm (I sometimes have the strange and uncomfortable sensation that I am working in a previous professor’s living room), are a pair of hawks. They nest in the spreading oak trees that shelter my building and subtly terrorize the campus. You sometimes hear them cry, and, occasionally, you see them pop down brazenly onto the lawns. They are a wicked couple. During the semester, I have seen them snatch fat squirrels off of trashcans, then dangle them cruelly in the air from low heavy limbs. It is a frightening sight and only a few of the students look up to notice this apt metaphor for the economy ahead of them (there is, incidentally, a popular Facebook account run by students, @ECUsquirrels).

Now, the hawks completely rule their realm. Unlike the mythical dolphins of Venetian canals,1 they really exist, and they are my only campus companions in the late afternoon. I do not fear them. I see in them strength, grace and light: in their cries, the breath of spring; in their tails, autumn leaves. In Revelation 6:8, death, pestilence, and wild animals all bring destruction upon civilization. Here, the animals are antithetical to the pestilence of our time.

Whitman, also, saw the value of hawks. In the concluding stanza of “Song of Myself,” at the height of his reverie, he delivers what could be the most famous –and parodied—phrase in his entire oeuvre: I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world. This line echoes in sound and meter a reference to the spotted hawk just a few lines previous, which swoops by and accuses him:

The spotted hawk swoops by and accuses me . . . . he complains of

my gab and my loitering.

I too am not a bit tamed . . . . I too am untranslatable,

I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.

The last scud of day holds back for me,

It flings my likeness after the rest and true as any on the shadowed

wilds,

It coaxes me to the vapor and the dusk.

In the film Dead Poets Society (1989), in a well-known scene, a high-school student played by Ethan Hawke has his poetic soul coaxed out of him by his teacher, played by Robin Williams.The teacher eggs him on to riff on Whitman’s barbaric yawp. The scene begins with Williams pointing to a picture of “Uncle Walt” on the wall, then fluttering and circling and holding Hawke’s head in his hands, and it ends with Williams couched beneath the boy as his speech takes flight.

I am reminded, also, of the young William Wordsworth, who, in his own song of myself, the autobiographical Prelude (1805), rambles in the hills near Hawksmoor in the English Lake District. There he escapes the “unaimed prattle” of a late-night party and walks home at daylight through fields under mountains

… as bright as clouds,

Grain-tinctured, drench’d in empyrean light;

And, in the meadows and the lower grounds,

Was all the sweetness of a common dawn,

Dews, vapours, and the melody of birds,

And Labourers going forth in the fields. (IV.334-39)

At this moment, Wordsworth becomes a “dedicated Spirit” to poetry: “On I walked in blessedness, which even yet remains.” I realize how lucky I am to have found such a time and place to labor in, however bitter and mean this crisis becomes.

Whitman, Marvell, and Wordsworth in my heart, I walk home again through the five-o’clock shadows under the spreading trees of a gorgeous day in the South.

1.“The imaginary dolphins of Venice became, for a moment, a way of projecting ourselves forward into a world beyond the coronavirus crisis — a world where we have learned something, and been changed. We would all like to imagine ourselves as the survivors at the end of the disaster movie, venturing outside for the first time in months to discover trees growing through the abandoned streets, the birds and bees making their music, dolphins frolicking in the canals, the lion lying down with the lamb.” Andrew O’Hehir, “There are no dolphins in Venice: But the vision of a better world may sustain us.” Salon. March 22, 2020

Leave A Comment